Interview by Farran Golding

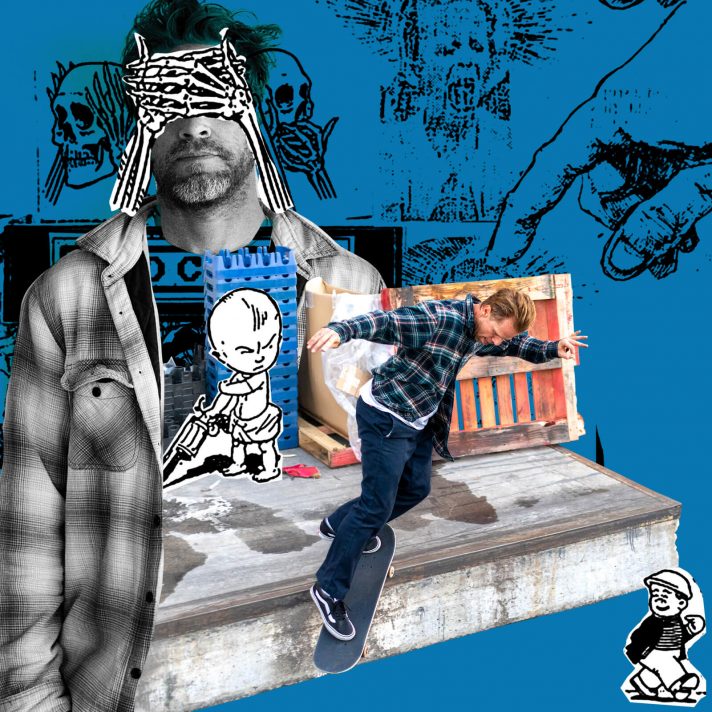

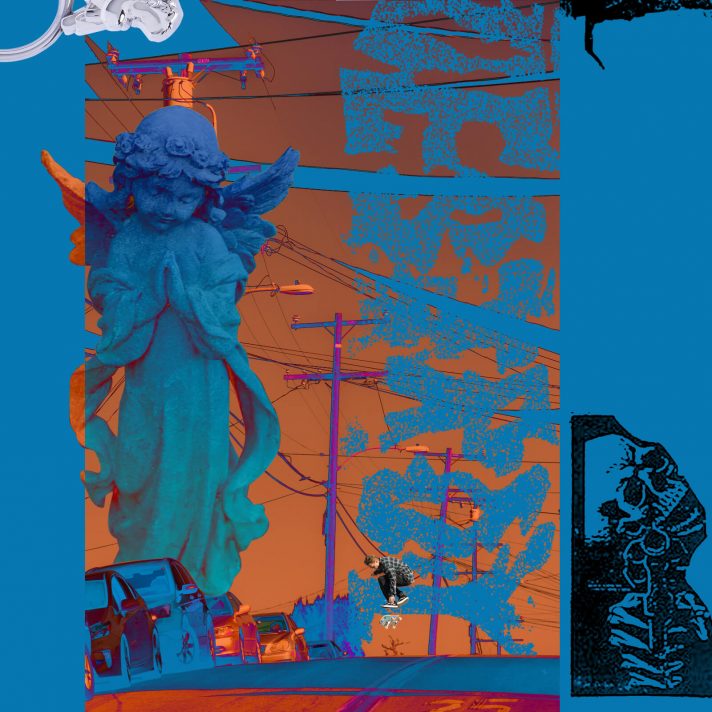

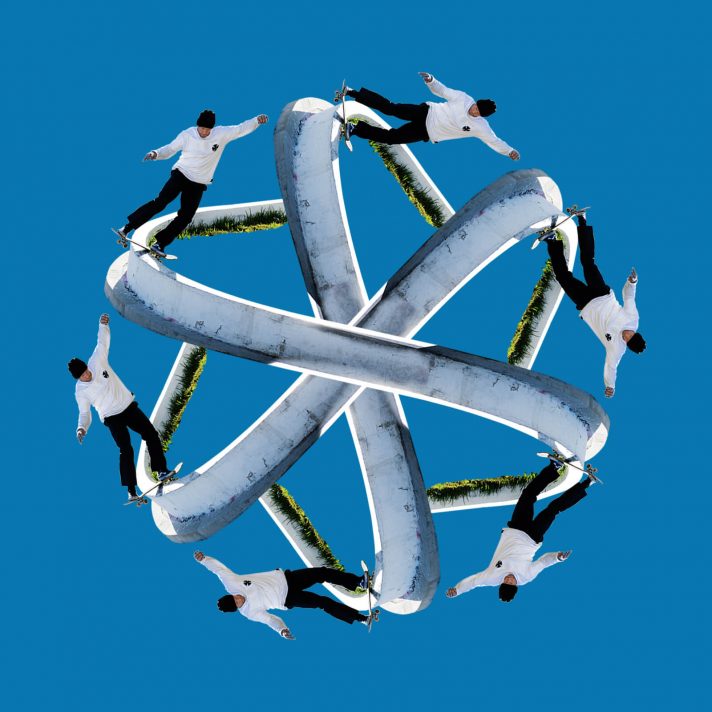

Collages by Requiem For A Screen

Original Photography by Anthony Acosta

The amount of people who have been able to pull off skate careers spanning over two decades is low. And in the skateboard-content-creation biz, we often fall on this assumption that these skaters have answered all the questions already, e.g. what can you truly unpack that Chromeball hasn’t?

But that’s false. Because the reason this group has been able to endure through the years is their prolific adaptability. The perspective of someone at the start of their third decade of a skate career is even different than it was when they were headed toward the latter half of decade two.

With A.V.E. on the horn for the “Favorite Spot” segment (thanks everybody for the kind feedback, by the way), not digging a bit deeper felt like a missed opportunity. Farran spoke to him on where his perspective on this thing called “professional skateboarding” stands today, entrenched in the third decade of doing it.

Aside from a ton of stress in the early days, does fatherhood share any similarities with running a company?

I’m 42, so I approach everything with a heightened level of responsibility. Having a kid sets the bar to be prepared every day, for whatever I need to take care of. I’m up at five in the morning – pretty much every morning.

When you start living your life that way – like I have friends who might be going through things in their personal lives, they don’t have kids but they might have a girlfriend — and I’m like, “Dude, I get it, but your time is so free.”

Once you have a kid, the responsibility to show up, be there, and work through anything is totally different.

The F.A. kids aren’t kids anymore and you and Dill have watched them grow into adults, firsthand. They’ve accomplished so much. Do you take any pride in your role there?

I’m extremely proud of all them and it’s incredible to see them start out as, yeah, kids who were just in the mix. Or even flowing some of them when we were still on the Workshop. Now that they’ve gone off and become these individually incredible skateboarders, and have even branched outside of skating – whether they’re making music or opening a restaurant — to have witnessed that and been a little part of it with all of them, it blows my mind because they’re such uniquely great people.

When I think of what a maniac I was at their age, they’ve really got their shit together too.

Is your team having a lot of say in, well, the team something of another carryover from the Workshop?

Skateboarding has always been very tight-knit whether it’s in friendship circles or whatever, especially coming out of the nineties when it was really small. There was something of a narrow mindedness for some of the younger skaters, a rigid view of what was deemed “good.” I grew up with that. With skateboard companies and the people who ride for them, it’s always been tight-knit regardless.

It wasn’t something just at the Workshop or over here [with F.A.]. Look at Girl and Chocolate: that squad was so tight for 20 years. It was so elite and those guys were together through multiple variations of those brands.

There’s been a little bit of manufacturing “super teams” over the years, which is so at odds with how board companies have evolved over the past decade. Nowadays, the appeal is in seeing a genuine connection between the team.

Definitely with shoe brands, you can get the “super team.” There have been some board companies along the way that were put together with dollars at the forefront, versus a group of people who organically ended up creating something together.

That’s how I look at F.A: “Man, this wasn’t something we thought of. This just happened.”

There are things in skateboarding which exist because there’s a business end of things and I get that. But there are moments which give you the feeling of being where you’re meant to be, doing what you’re all meant to do.

It’s the way things worked out over the past seven-or-so years that we’ve been doing F.A. as a board brand. There’s an authenticity to it, which I think people see with the whole squad that’s now a part of us and how they became part of our life as young kids – and even how mine and Dill’s path weaved back together after having our own issues with life outside of skateboarding for a while — it’s been rad.

Jumping way back, you’ve talked about not liking your part in Photosynthesis (2000) because it didn’t feel like you were pushing yourself. Whereas fast forward to The DC Video (2003), and you were “setting the bar for how hard you can work to make a video part,” according to Greg Hunt. Was there a lot of intention behind it or were you just flat-out trying harder?

The DC Video is weird because I feel like I didn’t understand what hard work was until I was in my mid-30s. I still had youth on my side and I certainly wasn’t very focused, in a sense. Shit, how hard is to go out and skate everyday – hungover or not – when you’re fucking 20-years-old? It ain’t that hard.

Jason and I, we’d done quite a bit of skating for a couple of years, leading up to Photo. I think we were living together, we’d just come from 23, we were doing stuff with 411, we did Feedback and then, literally, while we were doing Feedback, we already knew Photo was on the go. We’d done the Alien “Industry” section, and by the time it came to Photo, I was really burnt out. The passion was a little weak for me.

Then, DC, it took a little while to get into the groove, but I think I broke through a slump, which had lasted throughout Photo and even into The DC Video because it kind of butted up against it. I got it done, and I know I did it better. In moments of time, I worked hard on that thing, but there were moments where I didn’t. I feel like I evolved as a skater through that, a little bit. I’m definitely more proud of what I did in The DC Video.

You and Greg Hunt have a pretty remarkable relationship which starts The DC Video. To still be in it together all these years down the line –

Again, Greg’s one of those things I was talking about which just happen along the way: “This is meant to be this way.”

Having one of the best skateboarding filmmakers and becoming a close friend of his — dude, all the projects we worked on over the years, you couldn’t have placed that. These are different companies and for him to end up in these places all of a sudden, making videos, one after another, us together – it’s unheard of.

It was Transworld when I first met him…

Your i.e. line at Paral·lel was the first thing you ever filmed together, right?

Yes! That was the first trip we went on.

So you’ve got Transworld. Then, DC wanted to do a video and Jamie Mosberg, who made The End, was hired to start filming it. I’m getting in the weeds here, but that was hard because he was trying to do it with 35mm film. Then, Joe Castrucci got hired to do The DC Video, because the Mosberg thing wasn’t working out, and Castrucci was trying to do Habitat, some of the Workshop graphics – I believe — and do The DC Video. So he burned out real quick.

Then Greg came in.

I can’t remember the timeframe from i.e. to DC, but we did that for three years. Then, he jumped over to the Workshop and we did Mind Field. Then, after Mind Field, for him to end up at Vans and into Propeller – there’s no connection between these things!

I mean there is, because it’s skateboarding, but to end up with him was a perfect storm. There’s nothing I did. I skated and we ended up together, making these long term projects. That’s definitely mystical as far as how I perceive it within my career.

Between that green bench and the USC Ledges, you had a good run with grinds around corners that carried into the rest of your career, too. What drew you to curved ledges the first place?

Originally it was watching Guy Mariano’s part in Mouse. When that came out, and he was going around those curves at USC, people weren’t doing that shit, really. Especially those tight ones. There was something about that and then the feeling too — when you do go around — it’s one of the raddest.

You started working on Mind Field around 2005. Then 2007 comes along and brings Fully Flared – this continent-spanning, blockbuster of a skate video. Meanwhile, you guys are in a van driving around the midwest. Would you say the stakes got pretty high for what was expected of a skate video towards the end of the 2000s?

For sure. I look back on that and I wouldn’t trade any of it for anything, but the shit people put themselves through, and the length of time it took to make those things, is fucking incredible. I’d come out of them a different person. Literally. Especially getting into Mind Field and Propeller.

Keeping that persistence going for three, four years — how I’ve always equated it is that a boxer will go to their training camp for a few months leading up to that fight. They do that fight and they rest for a second, regroup, look for the next one and start building themselves back up. But with skating and making videos at that time, you’re always in that fight until it’s over, so that’s how everybody approached them. People lost their minds doing these things. That’s probably why Greg and I worked well, or look at Guy and what he was able to do with Ty [Evans]; they’re no different.

I’ve watched Greg dry up puddles in the middle of the night by parking a van over a wet spot and revving the engine. When you’re sitting there and that’s for you, it’s midnight, and you’ve been in the van for twelve hours – you’ve almost lost your mind just by the time you’re in that situation.

Then when it comes to trying the trick, when that much has already gone into it…

You have to put in the effort, the work.

That’s the thing and this has happened to me: videos come up, you start going on these trips and sometimes it takes a minute to lock into the groove. Maybe you haven’t been in that groove, and when you get into a situation where maybe you aren’t at the height of motivation yet. It’s a lot of pressure.

But I’ve been in the place where I want that pressure, like: “I’m skating. This is my focus. It’s 1 A.M. and we’ve been in the van all day? Let’s go.”

I just want to suffer at the highest level. I’m ready and that’s what I want to do. Then, it’s fine when things are that heightened.

I’ve been in every mindset you can be in during these things, and at the end of the day, it’s pretty gnarly. At least it used to be. Things aren’t like that as much with videos these days.

For better or for worse?

A little bit of both. Everything’s got a side to it.

After years of doing that, back-to-back, this last F.A. project [Dancing On Thin Ice] was a breeze. It was really nice, it didn’t burn me out, I’m still skating a lot, and I want to keep skating. Even at my age, I felt it had as much of an impact as something I’d give my everything to for four years, and it was done within about twelve months.

It works better with where I’m at now. I couldn’t imagine making a video of the caliber which used to get made, over that length of time. But in the past, for myself – and I think for a lot of skaters – that commitment to making the best thing possible really makes you evolve as a person.

It’s cool to know there are moments in time where I really maxed out, saw the height of what I’m capable of, and it wouldn’t have come without those conditions.

On that note, you’ve got something of a reputation for one upping yourself and the rail at Columbus Park is pretty much a case study in that. What spurred on returning to it after Photosynthesis for the 5-0 and the nosegrind in Mind Field, then eventually hitting it switch for Propeller?

We ended up on a trip to New York and – as you do in New York – you go to the same spots throughout the day, every day. I thought it’d be cool to do something on that. I figured I could 5-0 it, so I did, and then I was toying with the nosegrind, knowing it’s possible.

I made it back to New York on one of the last trips for Mind Field, and I think I stayed there for the month. I can’t remember if I did it in one day, or it took a couple, but it felt cool to have that little throwback to Photo.

Fast forward to Propeller and just through being in New York, that spot was in the back of my head again, and I knew I could switch 5-0 that thing. And of course, it’d be awesome to have it as now we’re in this fifteen-year-span of having this spot in a video part.

The switch 5-0 was a fucking battle: multiple days, mixed into two different visits to New York. I’d originally tried it towards the end of a trip, then spent a few weeks going through Detroit, Ohio and all other these places, then I went back home to L.A.

That was a crazy time because Dylan [Rieder] was in his battle with cancer, and he was actually staying at my house with his mom. So I had come home for maybe a week, things were heavy there, and then I had to go back to New York to get this final trick. Towards then end of that trip, I tried it across a few days and got it.

Obviously skateboarding put you and Greg together in the first place, but there’s clearly an aspect of your friendship which exists beyond it. Can you dig into that a little?

Sitting in the car with somebody for hours upon hours, days upon days, you really get to know them. It becomes something where you both agree without even verbally agreeing about what you like, you know?

We have one of those relationships, and we had a lot in common regarding what we think is good whether it be movies or music. And that too, going back to skating, is what made it so easy for me to work with Greg. There are really good filmmakers and editors, but I’m not necessarily aligned with the end product, personally. Whereas with Greg, that alignment was there, so I never had to worry about it. If we had to do something, and if Greg was doing it, I can trust his opinion – even beyond skateboarding or filming.

There’s a couple of instances where people have hit a definitive moment in their career. It’s not an end point, but it’s climactic. Andrew Reynolds had it with Stay Gold, and I feel that you did too, with Propeller. Alongside the personal fulfillment that I imagine comes with that, is there a sense of relief in knowing you never have to go through that process again?

Not to say that I ever necessarily looked at it this way, but when you’re younger – skateboarding isn’t a competition – but you’re more aware of your position in it, what others are doing, and what “the level” is, maybe.

I think I reached a place of peace within myself after Propeller, where no matter what, until the day I die, when I lay my head down at night, I know I reached the pinnacle of what I was capable of – and that’s the most you can ask for in this life.

If you’re given a gift and you’re able to fully realize it, then you fucking did it.

Still, it doesn’t take away from me wanting — you know, “what’s my best now?” Like I said, this last video part was a lot of fun. It had its moments, but I enjoy a certain amount of suffering. Yet, there wasn’t that thing which drove me in the past either.

I talked to Gilbert Crockett recently and he was quite heartfelt in saying how filming video parts and shooting photos are his “tools” as a pro skateboarder. Granted, he’s a decade younger than you, but how do you feel in regards that, at this point in your career, when all dues are paid?

The hard work — as far as on the board goes — nothing will be as hard as the 2000s was with making those videos, but I still have that commitment to myself and my position in skateboarding. It’s like, “I’m going to do this until the fucking wheels fall off” because it doesn’t change.

Since we put out that F.A. video, I still go skate every day I can. I’ll put in a couple of hours, so mentally I’m already down to do that again.

I’m also motivated by fear. In my mind, I still get paid based on what I can do physically, so I’ve got uphold that end of it. And I’ve got a family. I’ve got all these things, so it’s like, “I get paid to skateboard so I better go out and do just that.”

I’m not as worried about banging out an interview and having a video part come out alongside it. But the way I approached the F.A. thing at the start was with the mindset of: “I’m going skating every single day, whether I’m sore or not for a year straight. It’s going to be kind of torturous at times. At the end of it, we’ll see what there is.”

How does your perspective on progression differ nowadays compared to when you’re “in the window,” as you might call it?

I mean, now, maybe my progression is that I did a switch crook to halfcab flip on a table that’s a couple of inches higher than the one I did in Propeller – but in my 40s – you know?

I don’t stress about it too much. At this point, I just want to enjoy skateboarding, so I enjoy putting in as much effort as I can, but not getting lost in the thought of “needing” to do the newest thing.

I build on the things that are already my strengths instead. A lot of days, I go skate and I do the same session at a park: back tails, front tails, back smiths, front smiths. I used to get super worked up, like, “I’ve gotta work on new shit!”

But fuck it, dude. I just want to go skate for two hours, land on my board a lot and worry about being strong in the things I can do.

What’s left for Anthony Van Engelen to aspire to?

I don’t know how to put it into words.

At this point in my life, I probably work harder and more consistently than I ever have at all of these things, so it’s maintaining a level that I expect from myself with all these blessings.

There are things that help me to continue to skate at my age, whether it’s working out at 6 A.M. or whatever, that I need to do it at this point.

It’s such a blessing to be here. A small percentage of people get to experience being a pro skateboarder even for a few years, let alone twenty. I can’t ask for anything more than trying to preserve all this stuff to the best of my ability. And to be the best person I can be for the people I work with, the team and my family, you know? That’s the long-winded version.

Loved this read. Huge fan for 20 years.

Canada loves AVE

Thank you skateboarding.

ALL CAPS FOR AVE

scratched the chrome ball itch, phenomenal interview with an all-time ripper. thanks for this, guys

This was great, thanks. More depth to it and more thoughtful than almost any magazine “interview.”