Skateboarder magazine ended in late 2013, but according to its longtime editor, anxiety about the magazine’s viability was present a decade prior. “Even in the early Skateboarder days — the mid-2000s — there were signs that magazines could be in trouble in the coming years. You had to switch gears and do everything you could to keep it going,” says Jaime Owens, who, following Skateboarder’s demise, became editor of Transworld Skateboarding. Transworld, of course, which published continuously from 1983 through 2019, now lives on as a web-only operation, due to its mix of 1.6 million Instagram followers and 400,000 YouTube subscribers.

We’ve been losing skateboard print publications for the past 20 years in a way that mirrors what’s happening all over media. While it seems inevitable, it’s worth listing what’s been lost. Gone are Transworld, The Skateboard Mag (disclosure: I was a staff writer for TSM), Skateboarder, Slap, Big Brother and Poweredge, along with numerous English-language titles from Canada, the U.K. and beyond.

Skateboarding will always be a cacophony of voices, and despite a healthy new wave of European skate mags, the loudest and nearly singular print voice in U.S. skateboarding is Thrasher. And yeah, as more than one person in the course of reporting this story told me: “Thrasher won.” (Thrasher editor-in-chief Michael Burnett declined an interview request for this story.) But stateside skateboarding in recent years is seeing an unexpected and exciting resurgence of printed skate publications that are offering fresh perspectives, more opportunities and new voices to the mix.

“We don’t worry about filling templates and can evolve every issue.”

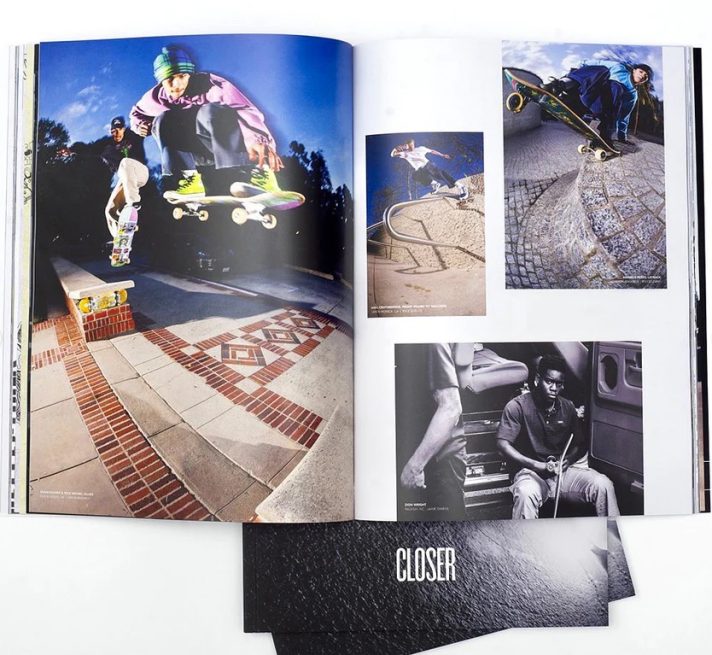

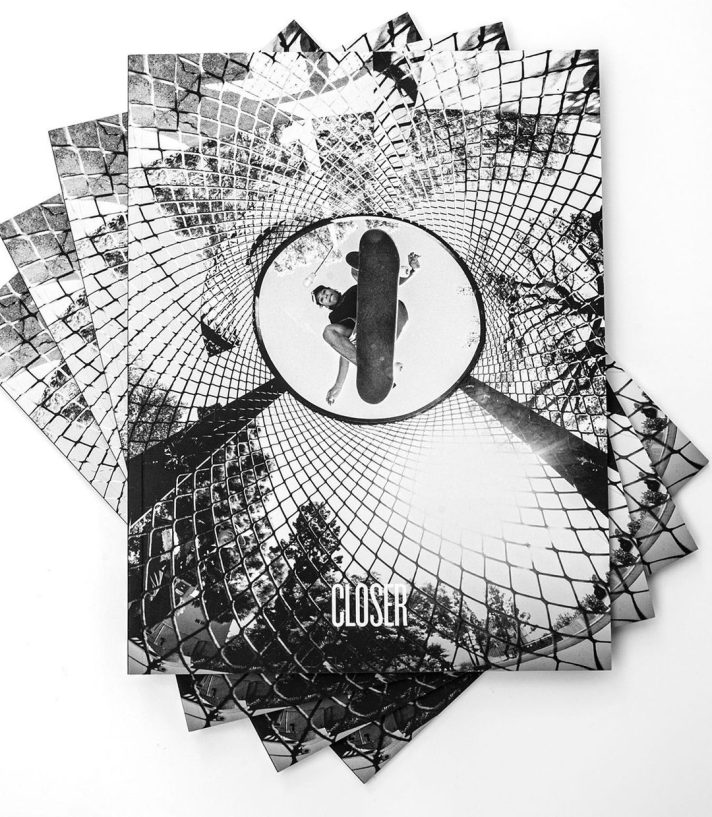

Owens is again editing a skateboard magazine called Closer. The latest issue, Closer‘s fourth, has Ryan Lay on the cover, shot by photographer Kyle Seidler. Features on the inside include interviews with Geoff Rowley and Ariana Spencer; a piece about Florida skateboarding written by Clyde Singleton; and a Chrome Ball Incident interview of Brian Lotti. “I’ve made skate magazines for 20 years,” says Owens, speaking from the Closer office, which doubles as the guest bedroom in his house. “I want to continue adding my voice to the lineage of skate magazines.”

“One voice isn’t necessarily enough voices,” says Kevin Wilkins, another former Transworld editor who was editor of The Skateboard Mag prior to it being bought by The Berrics (further disclosure: Wilkins was my editor during my time at TSM.) “There should be a counterpoint in all this stuff.”

Wilkins likens skaters’ urges to make videos and magazines to the same forces that make us want to skate. “It’s like being on a session – you want to be a part of it, because you’re adding to that social event.”

Whatever has shifted in skateboarding and general culture over the past decade has broadened who speaks in skating, Wilkins says. “It seems like there’s way more room in skateboarding for voices outside the male weirdo artist or the male-weirdo-jock-tech-god. Now, there’s room for a feminine voice and a gay voice and a trans voice and a nonbinary voice. It’s made skateboarding more open to expanding its culture.”

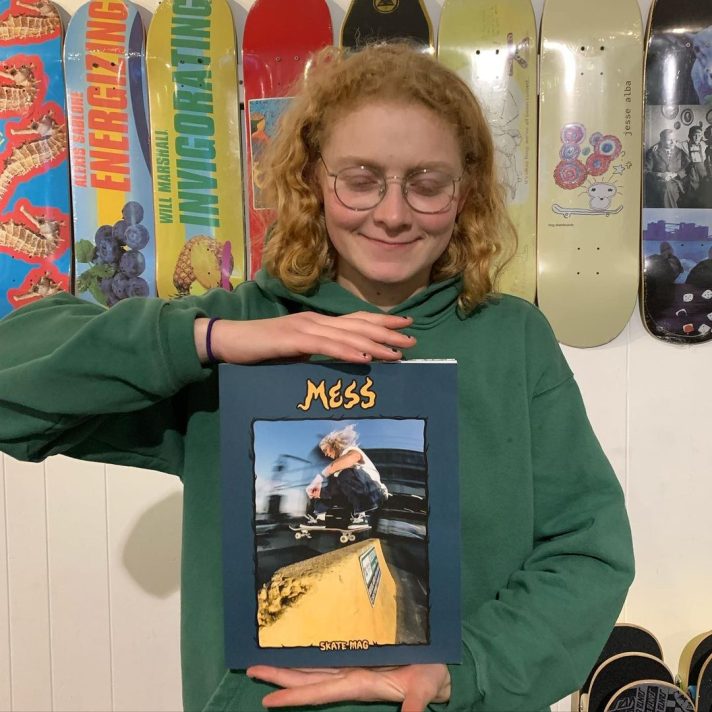

I grabbed the third issue of Mess magazine from the shop a couple weeks ago – Deluxe distributes it. Dustin Henry is on the cover, shot by Mikaela Kautzky. It includes items on Evan Wasser, Jackie Michel, Sam Narvaez and a ton more, with a “Words and Photos With Friends” feature by Sarah Muerle. “It’s more visual-based,” says Mess editor Shari White, who also makes videos for Vans. Mess is a continuation of Skate Witches, which White says she created for six years with current Mess editor, skater and organizer Kristin Ebeling; former Rookie Skateboards rider Jessie Van Roechoudt is also an editor.

“There’s a weird relationship between humans and things that are tactile.”

White says the shift from Skate Witches to Mess happened because the former was gendered. “This is a magazine for everybody,” she says. Its mission, White reads to me over the phone, “is to create a space for alternative conversations and content in skateboarding while highlighting relatable skaters from diverse backgrounds.” Or as White explains: “We were like, ‘Let’s bring everybody together.’ It’s super mixed and it’s just like skateboarding. We only feature people who we back and people who are allies.” The magazine, as intended, says White, is a bit of a wonderful mess – page by page, it’s unclear who and what will be coming next. “We don’t worry about filling templates and can evolve every issue,” she says.

Van Roechoudt says that living in Oakland and skating with the Unity crew had her thinking of starting a magazine. Krux team manager Alex White put her in touch with Shari White and Ebeling. “The idea came together to do something that was more fitting for right now,” Van Roechoudt says of Mess. “It’s something I wish had been around back in the day when I was in it.” With its focus on the visual, Van Roechoudt says Mess creates opportunities for both skaters and up-and-coming photographers to get a foothold. “There’s a lot of people trying to shoot and there’s not a lot of avenues to put that out.” That creative output, she says, creates more opportunities and expands skating – skaters get ads, skaters start new companies, there’s more ads to support new publications. “That whole ecosystem has a place to live.”

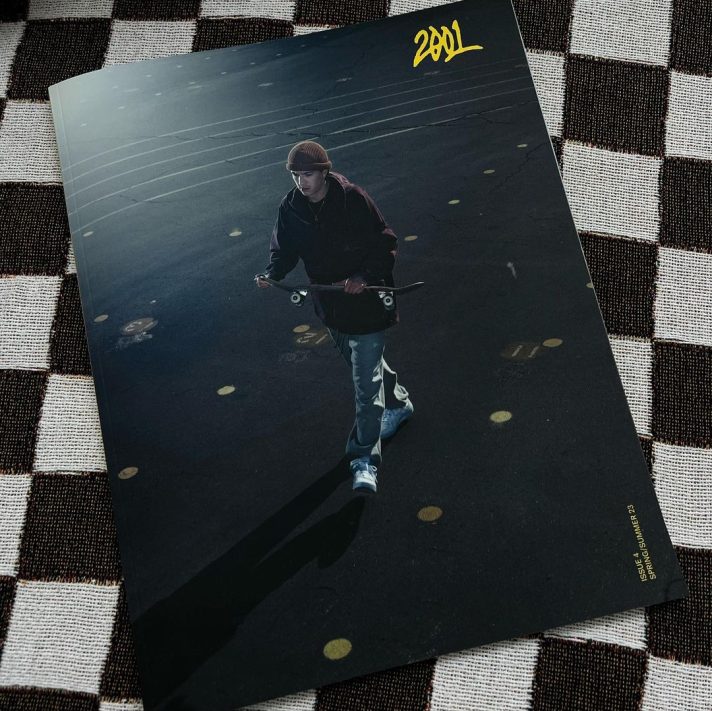

Skaters love material culture – stickers, videos, pins, old trucks, new wheels, bricks and chunks of granite, magazines. “There’s a weird relationship between humans and things that are tactile,” says Wilkins on the persistence of print. “There’s something about the friction of things rubbing up against each other and causing reaction.” My mail carrier, Roxanne, announced the arrival of four issues of 2001 magazine with a loud rap on my door. The bag was heavy and the magazines are huge. Photographer and 2001 founder Sam Muller says he makes the magazine 11″ x 14″ because those are the same dimensions as darkroom paper. “It had to be that size.”

“You should start a print magazine because there’s way more photos than there are pages in a magazine.”

A portrait of Diego Najera shot by Muller is on the cover of 2001 issue four. Inside is a 21-page interview with Najera conducted by Muller’s wife, Erika Houle, who has a background making fashion magazines and appears on the masthead as managing editor; there are 63 pages of photos; a 59-page feature talking to those who made the monumental videos of 2003; and an interview with punk band Meet Me @ The Altar. Both in terms of the magazine’s size and those page counts, Muller offers proof of concept: “The concept was to give a large canvas, if you will, to photographs,” he says.

Muller, who worked as a staff photographer at Transworld in the the first half of the 2010s, says he grew up in a household surrounded by issues of Time and National Geographic. 2001 refers to the year in which he got his first skateboard mag. It’s been narrowed to the March issue of Transworld from that year, with Jim Greco backside noseblunting the Wilshire 10 on the cover. That first TWS was transformative. “That really opened my eyes to this cool community that I want to be a part of,” he says.

Muller’s inspiration for starting 2001 echoes Van Roechoudt on limitations of space, “A friend of mine was like, ‘You should start a print magazine because there’s way more photos than there are pages in a magazine.'” That shared understanding has led to collaboration. Van Roechoudt says Mess will work with 2001 and other magazines to find homes for photos that don’t make it into Mess. “It’s all very complimentary,” Van Roechoudt says. “All of us together can provide a more complete picture of what’s happening in skating.”

As a Transworld alum, Muller says he remembers the skateboard magazine world as a sometimes “cagey environment” – the great skate mag rivalry, of course, was Thrasher vs. Transworld. This new environment is different. “There’s room for more perspectives and conversations than there had been in the past,” Muller says. “It just feels like skating. Since I was a kid, you go to the skatepark and you make friends… the sense of community grows.”

Covers, baby! They’ll never not be exciting. One in recent memory that really stands out is that of Closer number three, where Matt Price put his camera in a garbage can and Louie Lopez backside flipped over it. “I got lucky with that one,” says Price, who’s also had photos run in Mess and 2001, and does his own printed skate project, Golden Hour. He recalls Closer asking for something interesting; he wondered if the picture would be gnarly enough. That cover looks unlike any other skateboard magazine cover in recent memory. A diversity of covers and more skate photography seeing the light of day – and photos not looking the same as the footage of a given trick – fosters new ways of thinking, he says. “For kids on the verge of being creative, they’re going to see that shit and get excited.”

One day in late-May on #skatetwitter, Sam Korman, the author of the skate blog Waxing the Curb, posted a picture of a quote from writer Terry Nguyen that, in part, said, “Publications, print or digital, are created to capture a specific moment in the zeitgeist. Magazines are micro-societies, an attempt to formally recreate the spontaneity of social relations on the page.” Korman, my paraphrase here, wondered which skateboard mags this could apply to. I got him on the phone a week later.

“Michael Burnett has the hardest job in skateboarding. Putting out a magazine that big every month is insane.”

“I think it’s important you’re talking to a blogger,” Korman says before explaining how he thinks so much of skateboard media, especially online, have become aggregators. “It creates such a weird situation, where there’s actually no perspective anymore and it’s about making sure you are able to repost the same thing everyone else is reposting.” Whereas Mess and Free, with its pan-European perspective, he says, have done a good job of representing the ethos of a scene. To crib from that quote, they manage to recreate the spontaneity of social relations on the page.

Korman says provincialism in the skateboard industry often “doesn’t admit anything outside of skateboarding,” magazines included. “I don’t think it really speaks to the omnivorous tastes of skateboarders.” Who among us — back when — while at the Barnes & Noble newsstand, didn’t page through the latest issue of Thrasher, then end up noodling art, fashion or architecture magazines? Not everything, Korman says, has to be “who’s doing the gnarliest thing this month.”

The final issues of The Skateboard Mag in which my bylines appeared, about a decade ago, were tiny, with fewer than 90 pages. For reference, Thrasher Issue 500, from March 2022, is closer to 300 pages. TSM’s shrinkage was reversed for a couple years when it was bought by The Berrics; in late 2017, it was turned into Berrics Magazine, which lasted two issues. All that is to frame how happily surprised I am by this new energy in print. I wouldn’t have predicted it. Price, on the other hand, did.

“I’ve broken even on two of the four issues.”

“I started Golden Hour in 2018,” he says. Price says he realized that, for around $5,000, he could print a couple hundred high-quality magazines, do a photo show and find a sponsor to foot the bill. “It’s easier than people think,” he says. “I do it like a little art project.” Golden Hour is four issues deep over five years, and herein lies the hard part: putting out a printed skateboard publication on a regular basis. “Michael Burnett has the hardest job in skateboarding,” Price says. “Putting out a magazine that big every month is insane.”

Perhaps that’s why we’ve yet to see an attempt at a new monthly magazine. Closer publishes quarterly and Owens says he takes a similar approach to that of Price. “It’s a community-based project and I’m putting everything I can into making something of quality that skaters will appreciate,” Owens says. “When I say project, I’m not discounting it as a business, but it’s like an art project. I’m trying to put in as much passion and love of skateboarding culture [as I can], make it more than a business.” Shari White has similar feelings about Mess, which releases a new issue when the new issue is done: “This is a passion project, not a business.”

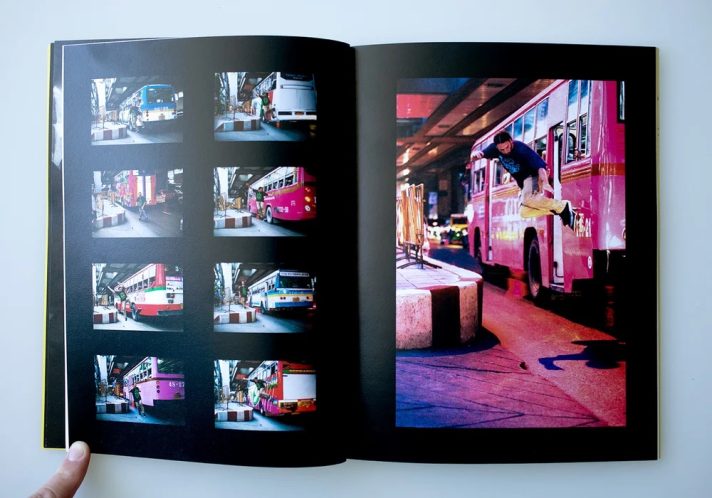

Muller of 2001 is even more candid. “I would say I’ve broken even on two of the four issues” he says. And yet, he also says the experience of making his own magazine has been reinvigorating. “The desire to shoot skating ebbs and flows, but now that I have pages to fill, it’s exciting to shoot,” he says. With that excitement has come more experimentation. “It comes from running portraits, reportage, and stuff photographed out pushing around that visually has nothing to do with skating, but is what it’s like being a skateboarder out in the world.”

Wilkins, formerly of Transworld and The Skateboard Mag, says the dream would be a skateboard magazine with no need for advertisers — it could do whatever it wanted. In our world, where ads are a necessary part of the game, he likens the skateboard magazine business model to an airplane: it’s up there, but if it’s got nowhere to land, it just circles. Owens says he’s taking a different approach to flying his skateboard magazine. Cribbing from a model that’s worked for decades to keep The Surfer’s Journal afloat, he wants Closer to be mainly supported by readers in the coming years. He says The Surfer’s Journal has cultivated a large subscriber base, relying on them for the majority of revenue with limited ads, and notes how the magazine continues, while familiar sounding titles – Transworld Surf, Surfer, Surfing – are no longer around. “[The Surfer’s Journal] outlasted everybody by not being fully dependent on an industry that continually fluctuates,” he says. I hope it works, and I hope there are other models that’ll work too.

For his part, Wilkins digs the open-endedness of it all, the circling. “It’s cool,” he says, “That’s what skateboarding produces. Misunderstood, unidentifiable everything. The tricks, the culture, the people; and I love that there’s these magazines.”

Shout out to 43 mag <3

Awesome piece

i’ve said too much

Nice article. I really miss a mainstream publication like TWS was, besides Thrasher. I had my first TWS magazine in 1991 and had been, let’s say, socialized on that kind of approach. However it was really difficult to get a printed magazine back then for us, Thrasher for us was always an alternative source, the contect was usually “punk” which had its on segment. But was a certain need for a professional magazine like TWS, professional in a sense of cultural approach, coverage about skateboarding. I’m really a big fan of printed magazines, I have a lot in my collection but yes, today’s mags are more likely in the small community segment. I like and appreciate Thrasher too, but to say that nowadays Thrasher is THE mainstream magazin of the culture is a little bit troublesome. The same “problem” I have with some of the “mainstream” European ags, that every time I read an interview I don’t feel like getting value out of it. Sorry for saying that.

I hope that there will be something like a burnout of the instant social media “culture” to have again printed value based, professional magazines like TWS was for a wider audience, that could include everyone, keeping on high the quality level of the content too.

As for my own taste, I like ads in the magazines, no problem with that. I remember even TWS mags in th elate 90s, earliy 00s being thick as coffee table books or Vogue’s, so there are plenty of content out there, don’t worry to fill issues from month to month, if your sight is wide enough.

T/hanks for the support!

I love magazines. Most probably don’t remember Concrete Wave, great catch all skateboarding magazine. It had slalom, freestyle and even ahem long boarding, but plenty of pool skating. It was a great magazine that I still enjoy flipping through today. And no mention of LowCard throughout the whole article?

well done, MIKE ! !

Burnett turned thrasher into transworld.

Juice is good in its demented way.

Great read. Great article idea. Happy to see print mags left and right in skateboarding. Some people never stopped making em and I used to snag tons from Theories of Atlantis back when I bought more stuff just because.

I loved Skateboarder, Transworld, Big Brother, and Slap tha most. Though Slap was a rarity in my area.

I’d say Thrasher survived by pivoting ta video (aye yi yi) early on and perhaps because their gear isn’t specific to skateboarding. It sounds “hard” and h*il satan is an easy cheesy gimmick to run to the masses.

Middle schooler energy thinking your tough throwing up horns I’m good.

I have never been much of a fan, myself. The photo quality isn’t great and the interviews aren’t to in-depth (lobby that at any of the major deceased mags, though). Also many subscribers are last to get the mag to their door; that’s some wack service right there.

They can say they love all types of skating but what we’re gonna see is big rails and skatepark flyouts from all the usual types.

The best, most in-depth, interesting, real life, relevant talk is not in a mag that can be purchased at the local nationwide grocery store. Chromeball, Boil the Ocean, Bobshirt, even here.

Shout out to Free 43 Stoops Grey North Solo TOA newspaper.

I am a Las Vegas local skate photographer and would like to provide photos for any magazine looking for photos of local Las Vegas skaters. Hit me up!