Interview by Farran Golding

Photos by Chris Mann, Rafal Wojnowski & Rich West

As we age, it’s easy to only remember the “big” changes: VX to HD, social media, Thrasher becoming the only magazine. The smaller ones are tougher to catalog, but when you think about it, had a substantial impact. In the not-so-distant past, “raw files” weren’t a “thing.” You couldn’t DM on Instagram. Polar was a small brand selling outline logo tees to the few who could get them. These things changing had huge reverberations, and in many ways, helped make “underground,” independent skateboard brands the dominant brands they are today.

Given our current mess where everything is being reconsidered — how we express ourselves, how we congregate as a community, how we shop — it stands to reason that a skate shop in 2019 and a skate shop in 2020-onwards will be different places. This is by no means to say they are destined to their current online-only incarnations, just that everyone who works in skateboarding has been given pause to contemplate what’s important to them, how they share it, and how they make a living off it.

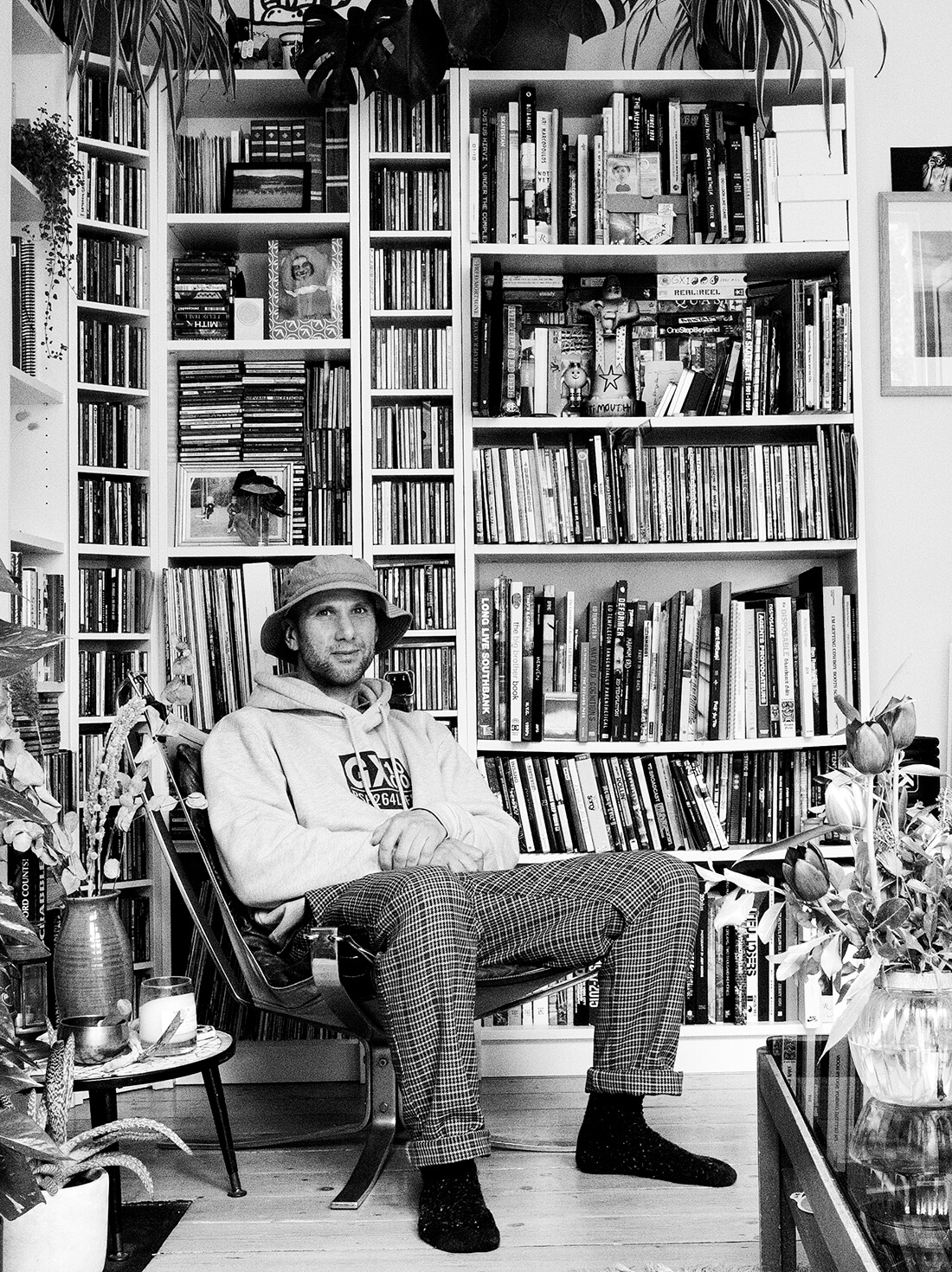

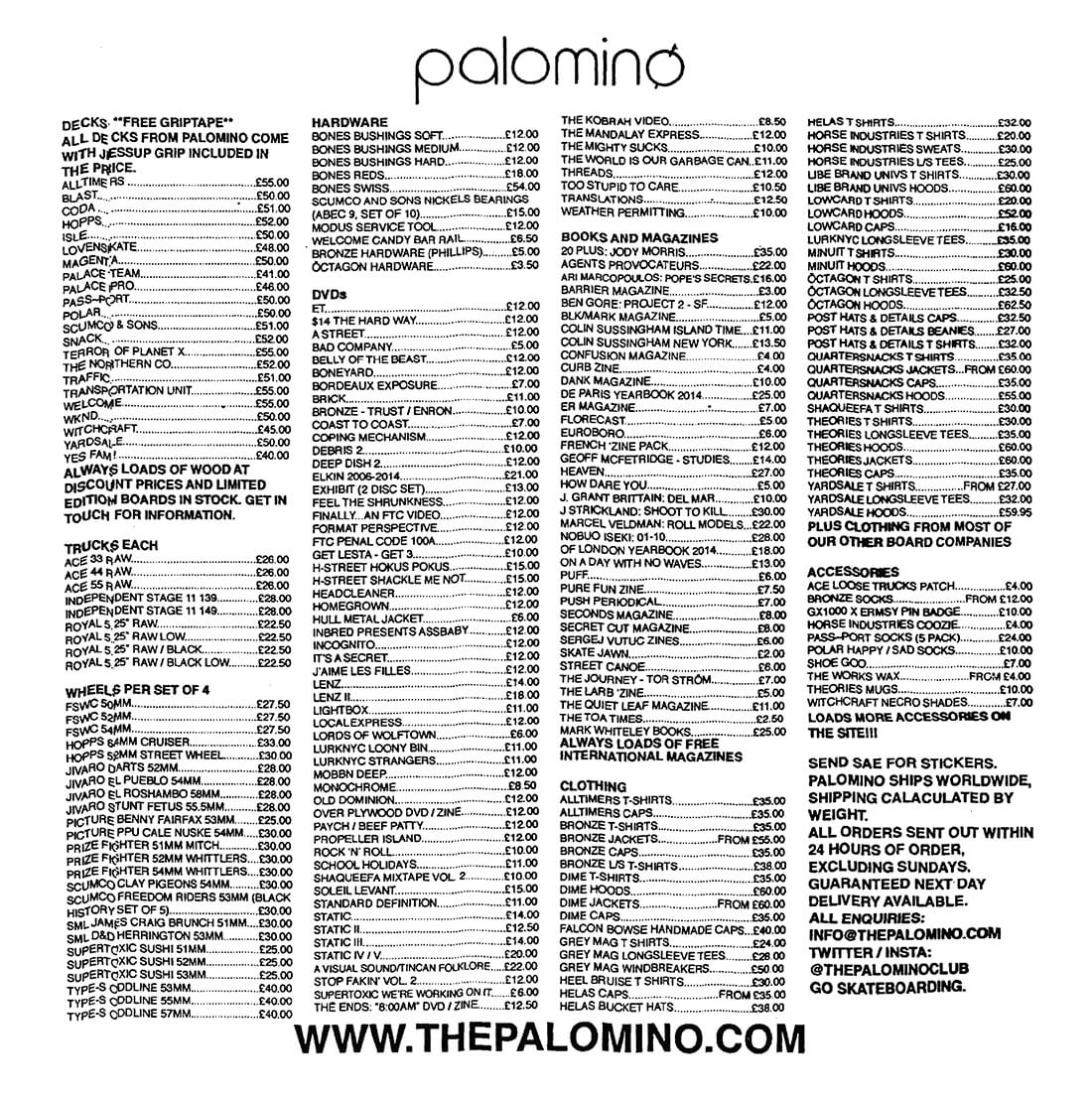

Nick Sharratt started The Palomino eight years ago, as a curated online skate shop focused on independent DVDs and publications, backed by the ethos of the most knowledgable, least condescending shop worker you ever had the pleasure of asking a dumb question. The Palomino feels like it anticipated many of these changes from when “independent” brands were still synonymous with being small in reach. We had our U.K. correspondent, Farran Golding, talk to Nick about how he made it work.

You’re of the generation when physical media was the only skate media around, but were you hooked from the start?

Before I started skateboarding, I was obsessed with magazines. Once I knew skateboarding magazines existed, I was buying them. If I couldn’t afford them, I’d pretend to read one and swipe the free sticker. I only skated for a small period of time when R.a.D [Read and Destroy] was around, but when Sidewalk appeared [longstanding U.K. magazine, 1995 – 2018], it was every issue for me. I’d read every article three times over.

The first videotape I would have bought, ever, was a skateboard video because I had no attachment to videos like I had to magazines. I bought Best of 411 — Volume 2 from a shop where my mom lived. I have no idea how many times I watched that 411. I’d put it in the VHS player, watch it, rewind it, watch it again, go skating, come home and watch it again.

How’d you find skateboarding?

It could be through Back To The Future, but I don’t know if I’ve just invented that from reading so many interviews that cite it over the years. I skated for about a year when I was nine or ten, which would have been ’87, ’88. I have no idea what sparked my interest again, but around 1994, ’95 I decided to get a board. That was when the proper obsession began.

Photo by Rafal Wojnowski

Fast forward, in 2009 you moved to London and were working as a carpenter. The Palomino was born out of your interest in DVDs and zines from all over the world, with you grabbing a few extra copies to sell to make up for the shipping expense. How were you discovering stuff back then?

The shop started in August 2012, but it was about a year in the making. Ben Powell [former editor of Sidewalk] was one of the first people I rang up and asked, “Do you think this is an idea that could have legs?” In early 2011, the internet — while vastly different to what it is today — was still the internet. If you liked Japanese skating, you could quickly find out about what’s going on in the Japanese scene.

I guess it was a combination of the Lost Art blog, the “Photos/Videos” section of Slap, and buying a new mag and following up on something I’d read about. Trawling the internet, I was finding stuff just by being a fan of it. At that time, the new wave of the likes of Palace, Polar and Magenta were in their infancy.

I’m not trying to claim I’m the only person who’d heard of this shit because there were a lot of dudes hunting out this kind of stuff. You’d go down the wormhole of watching a video, clicking a link in the description, which takes you to a site from some dude you’ve never heard of. It’s different to now, where the minute anything good is discovered, everyone knows about it.

“My misses wanted to kill me because it’s half six in the morning, she’s asleep and I’m three feet away pulling parcel tape off the roll, and hunting for a DVD before I get ready for work.”

There’s instant traction.

Yeah, which is brilliant for the people doing things. There’s no negative side to that.

The first three years of the shop, it just grew and grew because there was this group of people into the same shit I was. I made the terrible business choice of only stocking stuff I was into. It was arrogantly curated and the stock was purely my taste.

Take Bronze. At that time, there was only a limited number of people outside New York, who I was aware of, following what they were doing. I can only say that from my perspective as someone in London, but what I would also assume is the perspective of someone outside of New York back then.

It was like having a captive audience. I was the only person selling it, not many people knew about it, and not that many people cared. First Lost Art, and then Slam City also showed interest in these companies doing similar things. It was like we had to them ourselves for so long because there wasn’t this easy way of seeing something somebody is selling, and instantly being able to judge how popular it is.

Photo by Rich West

You were the first shop in the U.K. I was aware of that carried gear from Bronze and GX1000. Seeing them evolve and the videos become revered must be inspiring considering they’re part of the original motivation behind the shop? Josh Stewart once told me he believes the people who deserve success are those who “create the culture” — and you respect people contributing skateboarding on that level more than anyone I know.

GX didn’t make clothing then. The first GX video I had was their first ten episodes, which were on Slap, when it was a website and not just the forum — and only people into underground skate videos would’ve had any idea what GX1000 was. That’s not me trying to swing my dick around or belittle their position or output. It just was exactly that: underground. Same with Bronze. I’m fairly certain my first order was just copies of the 56K video in a little cardboard slip-case. Then, I saw some t-shirts and was like, “I’m super down for what you’re doing. People are into the DVDs so, hopefully, if people buy the shirts, it puts more money in the pot to buy more DVDs.” I would consider those both fairly big brands now. If they’re not big financially, they’re certainly influential, but [at the time] it was just crew videos.

The people I see having the strongest visual influence over skate videos, since The Palomino has existed, are Peter Sidlauskas and Bill Strobeck. Josh Stewart has said this before too: when Bronze became popular, there was suddenly a ton of derivative versions of their videos. Now, that has gone turbo for Bill Strobeck’s style of filming. Its beauty is in its simplicity and because of that, if someone tries to copy it, it ends up coming across as a weak imitation.

To come back to the question, it’s amazing to see how those companies have developed as the technology we use to share skateboarding has. I think it’s undeniable that Bronze and Dime are now more relevant than any of the bigger brands who were at the top of their game in a different era. You don’t need big investment to become big.

Photo by Rafal Wojnowski

How did it feel to take the plunge into running The Palomino full-time?

I had two years of it being a hobby, then a year of it being a part-time job, slowly turning into a full-time job — while I already had a full-time job. It was fucked. I barely had time to skate. I ate takeaway food because I didn’t have time to cook. My misses wanted to kill me because it’s half six in the morning, she’s asleep and I’m three feet away pulling parcel tape off the roll, and hunting for a DVD before I get ready for work.

There was no room for clarity of thought. I was making myself ill and I would’ve made myself more ill had I continued. It was like, “One of them has got to go.”

“Do I believe in this? Is it something I can make a good go of?”

“Fuck it, why not?”

My overheads were low and Stu [Smith], who does Lovenskate, was looking for new premises, which meant I could afford a little office space. All I needed to do was borrow enough money assuming the shop wasn’t going to pay me for six months. I had that much time to make it pay me a wage.

The shop was doing increasingly well. I’d buy three in each size of Bronze shirt and they’d sell instantly because it was just maybe me and Lost Art [carrying it]. There was no thought of making it physical. The idea of having a physical space in London just selling DVDs, ‘zines and Bronze, Dime, GX and Theories t-shirts in 2014 — you’d have to be insane.

I never considered myself “online only,” even though it clearly was. I didn’t start an online shop to compete with and undercut established shops. They just weren’t selling what I was into and I mean no disrespect there.

“It doesn’t have to be the ‘best’ if you know the motivation behind it is coming from a sick place.”

What makes you want to back a video or publication?

At the beginning of the shop, it was the fact something was little and done for creativity’s skate. The idea that it was relatively unknown was so exciting to me. I don’t want money to be the driving reason why something has been made. Obviously, anyone selling something hopefully makes a bit of money, but with a lot of DVDs and zines, people are just covering their costs.

There’s a nice parallel there between someone’s motivation for making something and your motivation for buying it, in the sense that it all comes down to the experience of creating and owning something tangible.

It sucks to have to have those conversations and I get self-conscious people might think I’m all about the money. That said, I haven’t not bought something I really wanted to have on the shop because there’s no way to make the money work. Every so often, something comes around and it’s like, “That just has to be in Palomino!”

It doesn’t have to be the “best” if you know the motivation behind it is coming from a sick place. Again, referencing interviews I’ve read with Josh, the skating in a video doesn’t have to be good for that video to be fucking incredible. You can be the best filmer in the world, but if there’s no relationship resonating from the people in the project and it’s just part, part, part — it’s really difficult to make an enjoyable video.

Photo by Chris Mann

How has the ratio of you contacting people about something they’ve made, compared to people contacting you shifted?

When I first started the shop, there was a long period where Instagram didn’t have direct messaging. So, it would be trying to find email addresses at the bottom of a website whereas now anybody can contact anybody.

Being entirely honest, pardon polishing my ego or whatever, but if people are contacting me to get their stuff in the shop, then that’s a good marker Palomino is somewhat successful and people respect it. Someone saying, “You stocked my ‘zine but my homie made this video, I’ll put you in touch,” is great for coming across things I’d miss otherwise.

You often stock bespoke publications, with a few personal standouts by Greg Hunt [Ninety-Six Dreams, Two Thousand Memories], Colin Sussingham [Boys] and Jonathan Rentschler [LOVE, Nowhere to Go From Here, Dill]. Where do you place the significance of those amongst “traditional” skate media?

There isn’t the zine culture of the 80s, where everyone’s making and mailing them to one another , but there are still people making them day in, day out, to share what their crew and scene are up to. Whereas in something like Jon’s Dill zine or 96 Dreams — creativity is driving them — but I think they’re also being made with the hope of turning a profit, appearing in places like Dover Street Market. That doesn’t make one any more valid than the other.

I see them as skateboarding maturing and self-mythologizing in a way that has already happened to other subcultures.

I really love books that have little skating in them. If we stick with something like 96 Dreams or Boys, so many of those photos aren’t of people skating. That Jon Rentschler Dill zine is photos of a dude in a restaurant, a bar and on a roof. I’d still consider it a “skate book,” but if somebody showed me a “skate video” where there’s no skating, I’d think, “What is this pretentious bollocks?” Yet, when it’s photography in a book, I separate those two things.

As skateboarding has gotten older, photography has remained intrinsic, which means the way photographs are presented matures alongside skateboarding. Time seems to move so quickly now, where I feel the way Boys is presented already feels nostalgic. And it’s nostalgic for something that to me, at my age, feels like yesterday.

“In Britain, I can’t think of another time where print was more buoyant and healthy. We’ve got Vague, Grey, Free, North and I’m bound to have forgotten someone.”

Boys is a good one in this instance. The crew in Colin’s book and those early Johnny Wilson edits are a reason I gravitated towards New York skating. Boys is already nostalgic to me because the subject matter is linked to a sort of coming of age era. Those dudes aren’t necessarily my favorite skaters, but that book elicits an emotional response.

Nowadays, we enjoy watching videos of people just skating as much we enjoy more formal, structured skate videos. Instagram has done that for sure, but I don’t remember people presenting skating how Johnny Wilson did, in a more relaxed setting with his first vlog-style edits, before then. Tricks not being landed, people having a cigarette on the curb, dicking about while someone is trying a trick for an hour. Now, there are entire productions presented that way. Somebody can correct me if I’m wrong, but I think Johnny Wilson deserves a lot more credit for pioneering that way of making skate videos. The reason Johnny’s videos have that vibe is because he wasn’t even trying to do anything — he was just filming his crew out skating.

Those edits are almost a middle ground between the photo book of nobody skating and a skate video. It’s almost voyeuristic: “I’m hanging out with these people.” But I’m not; I’m at home watching them on a computer. “Those edits had that feeling of a coffee table photo book” — did I just say that? That’s going to sound horrendous.

People talk about how the internet “killed” full-length videos and print, but without it, you wouldn’t be discovering the things which make the shop what it is. I guess The Palomino almost has a paradoxical existence in the timeline of how skateboarding media has changed.

Take The Nine Club. There are guests who work in the American skateboarding industry who think that print, on the whole, is fucked because Thrasher is now the only magazine in America. In Britain, I can’t think of another time where print was more buoyant and healthy. We’ve got Vague, Grey, Free, North and I’m bound to have forgotten someone. So many people are making things, be it the posh coffee table book, the Xerox’d zine or something in between like Paul Grund’s handmade concertina books.

However, the experience of watching something isn’t really any different. I still like to have the physical copy because I like being surrounded by it. I don’t take any pleasure from having a bookmark folder on Safari. It’s just a certain type of person that cares about the physical version rather than digital; enjoying the way those things look on a shelf and the tactile process of putting it in the tray and pressing play.

Community is one of the most important aspects of physical skate shops. How do you hope you’ve fostered that with Palomino’s?

I guess just by being a place for the nerds. The product has built a community around it, rather than anything I’ve specifically done. The people who are into the books, magazines and DVDs form the backbone of the shop.

Maybe there’s the fact that if you email Palomino, then you’re emailing me. There’s no accounts department or sales team, your reply is going be signed off from “Nick.” The only thing I can do personally to help that community is treat people with respect and help them in a way I’d want to be helped.

Where do you want Palomino to go from here?

I want to have an arm of Palomino that is like a skateboarding version of a record label. The amount of people who care about a physical copy is diminishing, however there are still people who care, but can’t afford to do it. If I can use the shop’s reputation to help fund the production, I’d be really happy. I have no experience in the world of publishing, but I now know of so many amazing photographers, so if I could help them put stuff out, then that would be another proud moment. It would be nice for the shop to contribute something beyond just facilitating the distribution of things other people make.

I have such terrible self-confidence issues, but I know I can say I’m proud of The Palomino as a whole. Putting on the premiere of Static IV was a pretty standout thing. If I’d have told the younger me watching Static for the first time that in X amount of years, he’s going to be helping orchestrate the London premiere of the last Static video…

Go on Park Shark! Absolute legend. Love from the Black Country x

So rad. Print will never die. Thanks Nick.

Polamino is the best! Stay strong Nick

Palomino is the sickest.

Legend

#1 bookstore for all my skate needs. Thanks Palomino!

Bizzle X

Best shop ever. Nick is rad as fuck.

read this and went and copped 5 zines from palmino, sick stuff

It was 5.30am not 6.30am