📝 Words by Mike Munzenrider

🎨 Collage by Francesco Pini

Deathwish am Davey Sayles was too ripped to rip. “I couldn’t skate the first month, I was so top heavy, I was swole,” he says. Six years ago, Sayles quit college football. He took a three-day bus ride home from West Florida University to Vista, CA. At 5’10” he had a playing weight for the Division II Argonauts of 220 pounds. Sayles says his skating weight is 50 pounds lighter. “It took me three months to slim down.”

The 28-year-old says he was a skate rat turned running back who was a natural on the football field. Sayles says he played because his family has a history with the sport and that he broke records at every stop in his gridiron career; he walked away from it while having pro prospects in Canada. Still, he says, he wasn’t able to be himself as a football player – for years he watched from afar as friends like Rowan Zorilla succeeded as skaters, stacking clips and turning pro. Having given up on football, Sayles says he wanted to prove himself as a skater. And he has – check him out in Baker Has A Deathwish Part 2 for proof – cutting a fascinating career arc along the way.

Davey Sayles in in Baker Has A Deathwish Part 2

Skateboarding hasn’t always been so cozy with sports, and vice-versa. From the late 80s through around the late 2000s, so-called jocks didn’t like skaters very much, but more importantly, skaters were loath to do anything that might get themselves called a jock. “I was a complete little jock kid,” says Davis Torgerson, former Real Skateboards pro from Minnesota and current Asics skateboarding team manager. For Torgerson, 34, the end of his sports life came in eighth and ninth grade; he was done playing basketball, baseball, hockey, soccer, football and golf. “[Starting skateboarding] was a complete identity shift, shunning that mainstream sports aspect but also loving skateboarding more,” he says. It’s a familiar story for skaters of a certain age, told in numerous Transworld magazine interviews of old, but not so much anymore.

Sayles’s story is one example of a shift in skate attitudes toward sport. Then there’s the aforementioned Zorilla, who marked the release of his second pro shoe for Vans with a baseball game; The Bunt podcast, which mixes skate interviews with sports fandom, is two years deep into holding a basketball tournament for skateboarders, the Bunt Jam; Tyshawn Jones earlier this year cross-promoted the release of NBA shooting guard Anthony Edwards’ Adidas pro shoe by getting a clip in it at the Brooklyn Banks; and Jenkem, just this month, released a video about hitting the pitch with a Chinatown soccer club.

Skating and sports are cozier than ever. How did that happen?

Matt Derrick, who for 20 years managed the DLX Skateshop in San Francisco and now works behind the scenes at Deluxe Distribution, says he started skating because of Marty McFly’s skateboard exploits in 1985’s Back to the Future. The 49-year-old grew up across the country in Saratoga Springs, NY, about 40 minutes north of Albany. “The appeal of skateboarding at that point was that it was different,” he says, recalling that being different resulted in flack from both jocks and rednecks. Derrick says a particular type of truck was to be watched for – it had a particular sound, too, and if it was seen or heard, a bottle might be chucked your way.

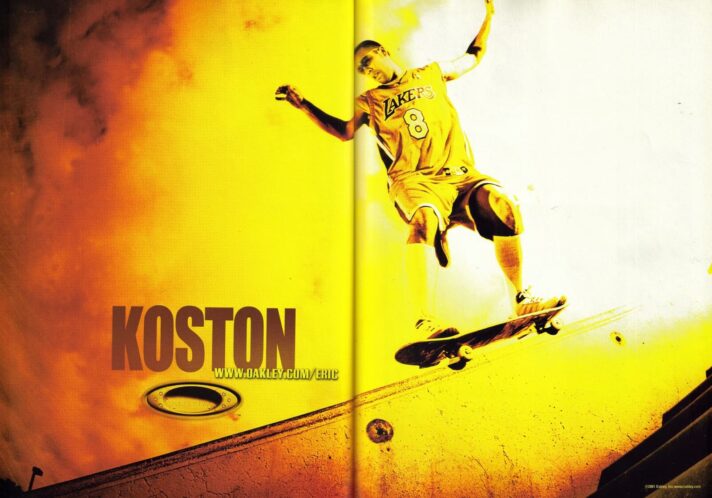

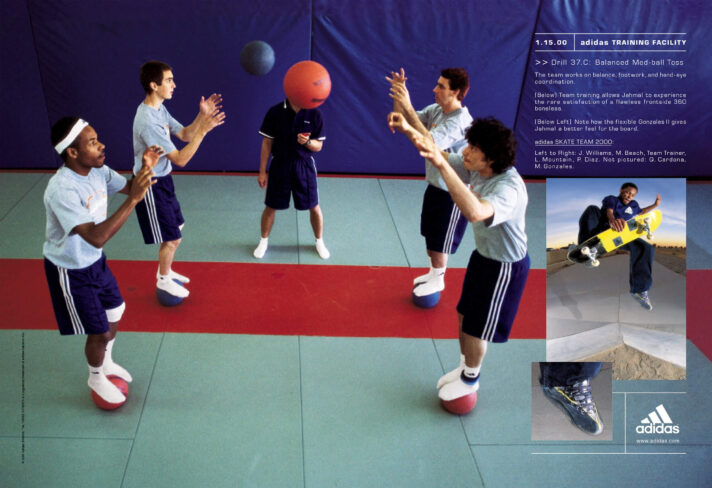

Skate-Jock Ephemera From 20+ Years Ago

Around the same time he started skating in seventh grade, Derrick says he joined his school’s swim team, hitting the pool through his senior year in high school. “It was just understood that part of going to school was doing the extracurriculars,” he says. Derrick swam a bit of everything, though excelled at the 100-meter butterfly. He’d skate in the summers and swim during the cold months. The swim team wasn’t a terrible place for a skater. “[I experienced] a little bit of outsiderness on the team, but the whole team was othered,” he says. “You had to be a little odd to think about swimming in the middle of winter.”

There are parallels between swimming and skating. “I liked that you challenged yourself,” Derrick says, “you’re on a team, but it’s not really a team sport; you’re trying to improve on your last time. If everyone collectively wins, that’s cool.” Because of all that, he says, he never felt like a serious jock – in the Upstate New York high school social hierarchy of his youth, Derrick says swim team guys were in a similar social strata as soccer players. A lack of college-level aspirations and a back injury, suffered during a game of handball his senior year at school, spelled the end of his swim career.

Some three decades later, from his perch at Deluxe, Derrick says skating’s growth is why attitudes toward sports have changed. “By definition, I’m trying to sell skateboards to as many people as possible,” he says. “The simplest answer is that with that many people out there, if you have a million skateboarders, a certain number of them are going to be into football, a certain number is going to be into baseball.” He notes that, for better or worse, there’ve always been sporting, competitive aspects in skating. “There’s still jockish elements to it: you can’t deny the hessian on the vert ramp yelling, ‘Do it fucking bigger, higher,’ isn’t jockish.”

Down in Frederick, MD, when Maddie Hazlett was in high school, if you were a jock, she says, the tables were turned. “The skaters were thinking all the people who played baseball were dorks,” she says, crediting the now-defunct Pitcrew Skateshop with creating a cohesive skate scene. “They fostered this community where this was the cool shit. If you went to baseball practice, you didn’t tell anyone.” Hazlett, a 31-year-old photographer, says that since then, her thoughts on athletes have evolved. The change began when she was 19 and landed a job as assistant team photographer for the Baltimore Orioles.

Though she played tennis in high school, another individual sport with a vague team aspect to it, Hazlett says she had a skater’s ignorance of most other sports, even on the first day of her new job. “I didn’t know all the rules of baseball when I shot my first baseball game,” she says. Working directly with pro baseball players, though, humanized athletes. “I think I found a lot of common ground that I didn’t expect to find. It was such a gamut of folks – just like skateboarding.” She also says she saw “how similar these high-level baseball players were to skateboarders – they were compulsive, even manic. Grown men playing with toys very emotionally …isn’t that just like skateboarding?”

Hazlett says skating’s changing attitudes toward sports mirrors the way skating has become more accepting in general, with space opening up for skaters who are women, queer or trans, or how skaters share skatepark space with quad-skater girls. “That wouldn’t have happened 10 or 15 years ago and that mindset and energy is breaking down barriers that shouldn’t have existed.” She adds, “I think people are realizing it’s just cool to have fun. Being outside and being active is fun.”

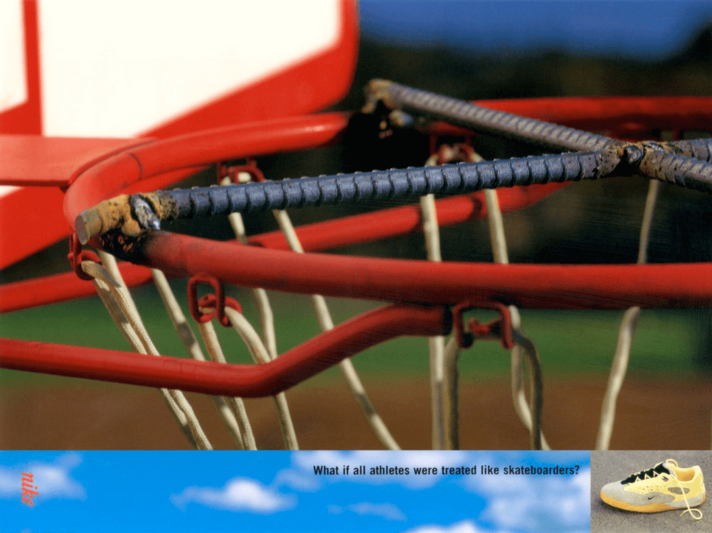

Pre-Nike SB “What If We Treated All Athletes Like Skateboarders” Campaign From 1998

How skating lines up against other sports is just plain interesting, too, even to the most successful of skaters. Sayles says Deathwish headman Erik Ellington will ask him about his sporting past on trips. “His whole idea was, ‘Damn, this kid played football? ‘Does your body hurt?’” Sayles says he suffered five concussions playing football and that in no way, shape or form is skateboarding tougher on the body than being a running back. “I’d rather be [skating] than being out there killing myself.”

Would NCAA rules of old have prohibited a student athlete from having a board sponsor? Ryan Herron, who went into his freshman year at Boston College on the Eagles dive team while riding for Convoy Skateboards, a Virginia brand, decided to never find out. “I did not tell my college team that I skated,” the 30-year-old says. This wasn’t exactly new for Herron; he says in high school he dived and also played baseball, with skateboarding filling in the cracks. “[I had] one foot in each world,” he says.

“There seems to be an inordinate number of skaters who used to dive,” Herron says. “I think those two really lended themselves to what I really wanted; I wanted to challenge myself.” Personal achievement goes far with skater-athletes. If there’s one thing he misses most about football, Sayles says it’s scoring touchdowns (it likely helped that a family member used to slip him $50 per TD).) “If I’m able to do something on a skateboard that I’ve never been able to do before,” Sayles says, “it’s the same feeling as breaking through five tackles.”

Herron says he pushed himself his senior year in college as a diver, which meant treating it like skating and working to progress. It worked, and he says he got a lot better, though post-collegiate prospects for divers are slim; the U.S Olympic men’s diving team is two spots.

It was around the time after Fully Flared came out, in the late 2000s, when Herron says he realized it probably wouldn’t dilute his status as a skater having interests outside skating. “I just remember seeing all those [Girl and Nike SB] guys playing golf. I don’t have any interest in golf, but it felt like it was ok now.”

That Transworld skater story arc of old continues to fade. Zamara Fabela says she ran cross country and did track and field growing up in Tucson, AZ, but that it wasn’t until she got to college at Arizona State University that she got her first board at 19. Now 24 and the community outreach coordinator for Skate After School, a nonprofit in Tempe, Fabela has a familiar-sounding story, but it’s about running.

“It was just very healing; it’s similar to skateboarding as a solo thing,” she says, noting she started the sport as an angsty middle schooler. “My brain is turned off when I’m running.” Fabela says she butted heads with a coach during her senior year of high school and the experience turned her off from the sport. She arrived at ASU and bought a cruiser that she used for transportation. The university has a Women’s Skate Club, Fabelia says, which had become dormant during the pandemic. She took it over and revamped it, which ultimately led to working for SAS.

Starting skating as an adult has been challenging, Fabela says, and her background running hasn’t always helped. “Skateboarding is so different and so hard,” she says, pointing out that she put pressure on herself to develop as a skater the same way she’d press herself to run a faster time. “I felt like I had to do [tricks] at a certain point.” Fabela says her personal benchmarks were mostly just frustrating, and that for 2024, she’s attempting to take a fresh approach to skating — saying she needs to “un-athlete” her brain.

Working with school-age children through SAS, Fabela says, is a good reminder of how unique skating can be. “[The kids] get so hyped learning that their boards can flip and its like, ‘you’re right, it’s so cool that your board can flip.’” She says skating clicks with certain kids in the program, while others will sometimes miss a SAS session for something like basketball tryouts.

Torgerson says he eventually found his way back to sports by re-embracing his often heartbreaking fandom of the Minnesota Vikings. He started golfing again. He’s played in both Bunt Jams, staying sharp on the court via L.A. pickup games with other skaters. “It’s another activity we can play together. We meet up, talk about skating,” Torgerson says. “Then we play basketball for two hours.” With this reporter assuming Sayles to be the best skater-football player, Torgerson tabbed The Bunt cohost Cephas Benson as the best skater-basketball player.

“If it’s not me, I don’t know who to say it is, probably sounds cocky as hell,” Benson, 35, says, adding he’s surprised Torgerson gave him the nod, since at last year’s Bunt Jam, Benson had hit him with a “crazy offensive foul.” Other damage was done during the recent tournament; Benson says he partially tore a ligament in his left knee while playing and that he hasn’t been able to dunk since. Benson came up in Toronto skating and playing basketball. After he finished high school, he says he was primed for a trip to California with high hopes (he says he had in mind a nollie heel backside lipslide down the Wilshire 10; clips back up this claim), but he seriously rolled his ankle just prior to the trip. “Next thing you know, I get down there and I can barely skate.”

That initial roll was followed by another, then surgery. While recovering, Benson says he couldn’t ollie, but he could run and play basketball; he was 20 years old and dunking both ways with both hands. “I couldn’t skate, so I just put all my physical frustration into basketball and really fell in love with it again.” He says his skate obsession turned into going to the gym. “I think it kept me sane. It was the first time I’d been off my board for a whole year.”

Benson’s ankle eventually let him skate again, and his gym obsession fizzled, he says, because of a comment from his Bunt cohost: “Donovan [Jones] called me Vin Diesel on a skateboard.”

When it comes to sports and skating, Benson says it has been the rise of social media that’s changed skaters’ attitudes over the past decade. He points to Ishod Wair and his “sustained greatness.” Wair can ball (Torgerson calls him a “silky lefty”), and on IG he posts about cars, fashion, photography. “He’s showing you all his interests online and then the footage always backs it up,” Benson says. “It’s healthy to have more than one hobby.”

Dennis Schröder of the Brooklyn Nets skateboarding before his NBA career. He’s still got it, btw

This cements it. Slow Impact 3 on 3 tournament next year.

The Ellington quote made me curious. Can we also get a piece comparing the wear and tear of skateboarding on the body compared to ball sports?

Barn burner of an article

in my world. RIP to tha doc

Interesting idea, but there are lots of claims and cherry picking examples.

And, a lot of the examples are from people on the periphery of the scene and people who aged out a long time ago, but refuse to leave since they can’t transfer their status in skateboarding to another field. They’re stuck and need to adjust skateboarding to fit their needs, just like many of those who cozied up to Gary Ream and IOC/Woodward.

the skate scene is a sus sausage fest.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I agree that it’s healthy to have more than one interest or hobby. Often times they compliment skating.

“Grown men playing with toys very emotionally …isn’t that just like skateboarding?” – so true, made me laugh.

Great and interesting read, MM. That collage rules too, FP. Reminiscent of old Eastbay catalogs.

is the actor, fool.

Ignoring the influence of corporate sports sponsors, Street League and Olympification makes this a very skewed and cherry picked narrative that leaves one with an overwhelming “OK, so?”

kinda thought the point of this was to talk about skaters actually playing sports rather than doing the olympics nike rant that everyone on slap has been browbeating about for 20 years

also Simon that is the most letterboxd review ass comment ever lol