Intro + Interviews by Adam Abada

Collage by Requiem For A Screen

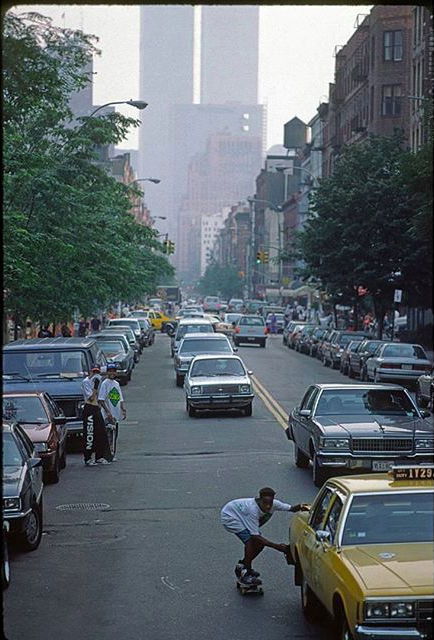

It is fitting that there are maybe the most skate photos of the Twin Towers featuring Keith Hufnagel and Harold Hunter: two of the greatest representatives of New York skateboarding.

Revisiting our series from two years ago, here are five more stories behind images of the Twin Towers in skateboarding, including many of Harold and Keith.

Looking into the stories behind them, I learned how essential they were to the fabric of so much of the skateboarding that has come out of the five boroughs. In memoriam photos of the Towers turn into stories about people and eras who shared some form of dual history with them, and in turn, ourselves. They remind us that if anything can be learned from difficult loss, it’s to always make the most of the time given to us. And that can be turned into hope and happiness, at least for a short time.

Tobin Yelland

How did you start shooting photos?

My parents had a couple cameras around the house; I got to use my parents’ cameras and fail a lot. I realized I really liked it. I skateboarded before I shot photos, so I already had a crew of friends who skated, and it was obvious to shoot photos of them. Then, it became obvious that I wanted to be a skate photographer.

Can you remember if you started using the built environment as part of your photograph compositions?

Of course, the skate trick is the most important: showing the takeoff, the landing, giving the trick full justice. My worst nightmare is not representing a trick properly and not giving justice to what the skater’s doing. The second element I want to find is something that is interesting, whether it’s a part of the spot, a street sign — just something in the photograph to give it another dimension.

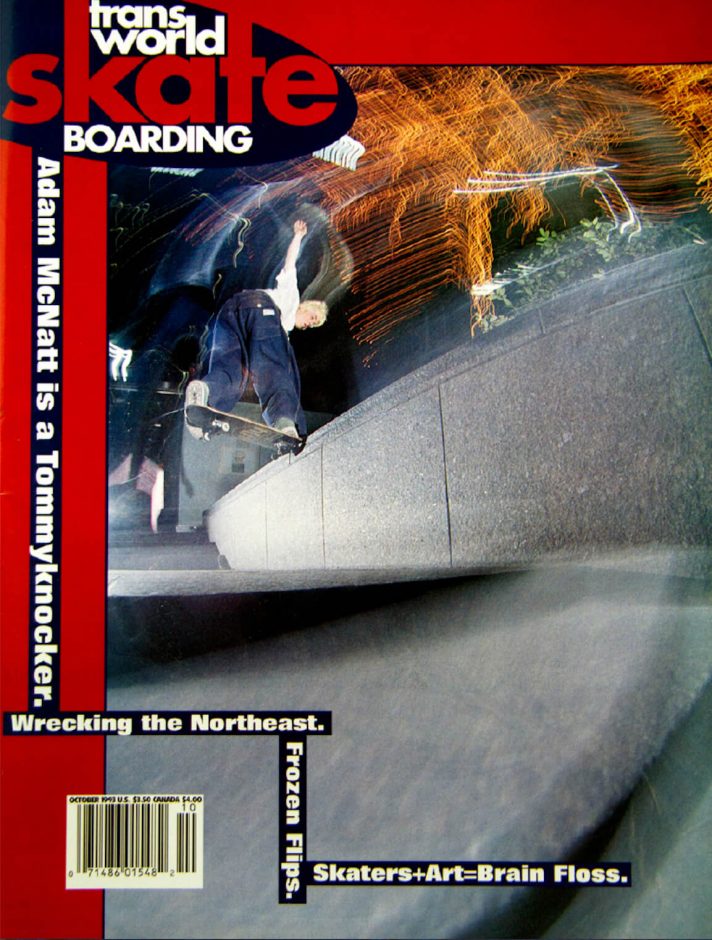

Do you remember taking this photo of Keith and the Towers?

I remember this day well because I got my first magazine cover that same evening — also with Keith. A front nose on a ledge somewhere in the city that I believe people call the Huf ledge now [Ed. Note: 46th and Park Avenue, though the ledge is gone due to renovation.] It was a huge deal for me.

I had just started as a professional photographer or whatever that means. Transworld really embraced my photography and were really nice to me. They encouraged me and sent me on trips. I knew Keith Hufnagel before going on that trip to New York. I shot that ollie on P3200 stock – a black and white film that’s rated for low light, and I shot it during the day. A lot of skate photographers were doing that at the time to get a really grainy look. I think I looked at it at the time and thought it was too grainy.

It wasn’t until Keith passed away that I looked at it more closely, scanned it, and printed it. So for me, it has double meaning. The Twin Towers were a really strong metaphor for New York and the world at the time and they went away. Keith also passed and they’re both memories now. I shot it from every different angle. This more direct one where he’s coming at the camera with the Twin Towers in the background just gives it “more.” Adding them into the shot – that decision – made it a much bigger photograph. It’s one of my favorite photographs, I think. It’s a beautiful memory.

The cliche goes in photography that photos freeze a moment in time. How do you think that principle represents itself here?

Photography, for me, at its best is a memory, a visual reminder of something that happened. Life changes so fast. This photograph of Keith gets into a memory of a time where, God, it was just so simple. We needed skateboards, we needed transportation, and we needed food. I needed to take pictures of skateboarding. We didn’t care about much else. Photography really brings me back to those basic needs and feelings. Fun times or shitty times with friends.

Charlie Samuels

How’d you start shooting?

When I was skateboarding in the 70s, parks started opening up, and our skate crew started getting filmed. I was wondering why they were standing at the bottom of these ramps filming. I felt like I could suggest a better picture or angle. Sometimes, I’d be able to take the camera and get on top of the ramp and get real close: I wished I was behind the camera shooting me.

When I went to the University of Maryland and showed their paper The Diamondback my portfolio, they put me on features. This is when there were maybe two or three skateboarders including me at a university of 40,000. And I found another skater. He was delivering pizza across the campus and I shot him. That was my first frontpage.

I graduated college and went to New York – I couldn’t wait to get there. It was popping with creativity and so exciting. I assisted over 100 different photographers in five years, fell flat on my face trying to go off on my own twice, then finally hit it with a picture of a skateboarder in The New York Times magazine. That was in 1990.

You have a lot of great photos downtown. How’d they come about?

In ‘89, after I shot a few ads, Kevin Thatcher from Thrasher called me up and gave me an assignment to do a second article [Thrasher had previously run an article on New York, but it mainly featured skaters from California] on New York City with the locals. He asked me to just shoot that summer and do a photo essay. Whenever I had a free moment, I went downtown or Brooklyn to shoot skaters. I did that at least once a week in ‘89.

You’d already been shooting with Harold, yeah?

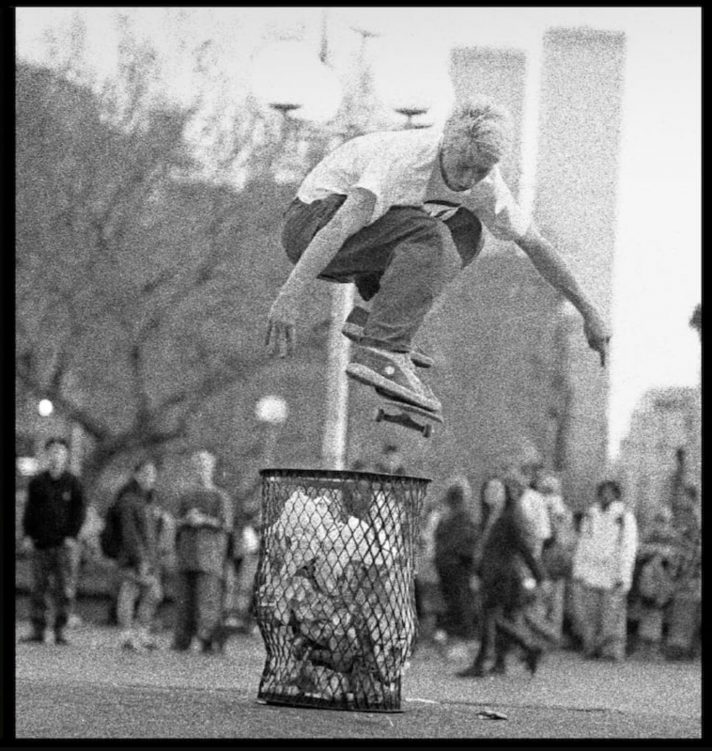

There was word around town about this kid who lived on the Lower East Side and did these really high, unbelievable ollies. I found him through Skate N.Y.C. – the shop that opened up at Tompkins Square Park. Not only was he an incredible skater, but he was just incredibly photogenic. He would not stop until he got the trick. Also, he kind of taught me how to shoot somebody. At the time – I’m shooting 36 frames a roll – I’m not really paying attention to people’s faces. I’m paying attention to the composition or the trick. But I’d get these rolls back of Harold and every frame had a different expression. I was like how does he know how to do that at 13 years old? It reminds me now of watching models work when I was an assistant at fashion shoots – models always change their expression slightly each time. He would do that. This photo of him at the Banks with the Towers, before he knew he was funny, was from a roll like that. This was always one of my favorites. He was such a graceful skater.

Do you remember taking the photo of Harold skitching with the Towers that’s in Full Bleed?

That was for that Thrasher photo essay. I remember it clearly. We would skitch a lot, so I had to get shots of that. I was trying to get shots of people skitching, and then I realized it needed something more. Every time we were going somewhere, I’d look behind us for a backdrop. And one day, sure enough, I looked behind us, and there was the Trade Center. I have a 200mm, explain some hand signals, go across the intersection, and see a box truck. I knew that was perfect cause I had to get up high to make the Trade Center more majestic. I scrambled up top, gave the signal, Harold skitched and I shot 12 frames. Then I asked him to do it again.

You mentioned the amount of shots you have of the Towers – what about that shot of Qulon Douglas that’s also featured in Full Bleed?

Qulon Douglas was another Skate N.Y.C. alumni who was mega talented. He was very quiet, shy and humble. Now he’s a comedian and funny as fuck. That shot was for Thrasher‘s NYC issue, but K.T. wasn’t much for artistic additions –– he wanted the raw and real “truth,” which I respect, but I didn’t care – Q had to be lit bright red!

We skated down to the World Trade Center looking for spots around it. By 1989, the guards at the plaza were on to us and at their most aggro during daylight. We spotted this five-to-six foot high granite wall that is not much more than a foot wide, with an endless runoff leading to the sidewalk – that actually survived 9/11 – across the street on the east side of the World Trade superblock. Q agreed to hit it, so I positioned myself underneath him against the end of the wall aiming my 20mm – my most published lens then – straight up while the rest of our crew did minor crowd control. I call this shot my American flag.

There’s a lot that’s changed since the time of these photos. How do you feel about the photos now?

Heavy, heavy chapters have passed since then. That was a time when we were really feeling like New York City was a skatepark. How can I put it – we felt unbridled freedom to do anything we wanted. We were basically a gang of athletic teenage kids traveling faster than anyone could run. No one could touch us. That was step one of the totally encompassing love of New York City.

On 9/11, when I rushed to my studio to get my cameras to take photos, I looked out my window and saw them downed. I felt like a part of my body was missing. To have that beacon and symbol not there anymore was unbelievable for me. It was a bad dream. I could never imagine they wouldn’t be there.

Harold was our first legend. He was sweet. As all hell. He gave his heart in many ways. He gave me so many photos from just that summer; it’s tough to put into words. I wasn’t really tight with him — definitely during that summer, we were friends. I never shot him after ‘89, really. I’d run into him afterwards more often than anybody: at parties, skating. He was always outside, always around.

I think what this photo also represents, is the transition from people either not caring about skaters or disliking them, to them becoming a bigger cultural thing. It was a transitional period in New York skate history. It was before it got noticed as a skate town. I think the photo speaks for itself. I’m humbled and flattered by what people have said about it.

Atiba Jefferson

How’d you start shooting?

I started shooting photos because of my love for skateboarding. I grew up in a small town in Colorado, skating with my friends, and a photographer in New York, Josh Wilder, inspired me to take photos. I fell in love with photography the first time I saw a picture being printed in the darkroom.

How did you start to use the environment around you in your compositions?

I studied the masters. The environment is everything. After the rules of shooting a skate photo – if they’re regular or goofy, which way they’ll be facing — then, for me, it’s how do you make this trick look as good as it is. I use my creativity to focus on the trick and then think about incorporating the environment. The environment is really cool to show, but the trick is most important.

Do you remember taking this photo? It was in Jersey City, yeah?

I was young and was doing things for Transworld. It took me a while to realize that you had to go out and make things happen. I wanted to show more New York and San Francisco street skating, so I went and did these trips. I knew Keith Hufnagel, and Keith always loved a posse. That posse was Chris [Keeffe], Ben Liversedge, Alex Corporan, and some others. I was getting to see all my favorite skaters live and in person, so those sessions were really cool for me.

Keith didn’t even skate that session. There’s also a photo of Ben Liversdge from that day, but no photos of Keith skating.

Do you remember considering the Towers when taking this photo?

Of course. You know, being a twin, I should probably represent the Twin Towers a little bit more. They were big, beautiful buildings to me.

I really regret this — I didn’t shoot the beginning of the sessions then. The getting ready, warming up, talking before the session. Now that it’s digital, people shoot it. But then, it was film and you weren’t gonna just shoot some random shit because that could be the frame that was the make. What we would do at the end of the roll is shoot something to finish it off, so you don’t get the make on that one. I had shot a beautiful photo of the Twin Towers themselves on that roll. I didn’t really realize I had done it.

What do you think about the photo now?

I feel so lucky that we were able to have those moments on film, this history. That’s fucking amazing. I feel very lucky to have people feel some type of way when they see some of my work. That, to me, is bigger than so many things I could have imagined accomplishing. Having these moments of all these people and places that aren’t here anymore: whether it’s the Towers, or Keith, or Keenan, many more.

It’s heavy, man. It’s an honor.

Adam Wallacavage

How did you start taking photos?

I started making zines. I was into comic book art and drawing things, and then I started taking photos with a 110 camera. I was wanting to take photos that looked like stuff I saw in the magazines. My friend Geoff suggested I put a door peephole and jam it into the front of my 110 camera. So I was taking these super small supermarket print skate photos with a fisheye – like two or three inch diameters. Then, I would photocopy that to make it bigger.

I got a job at a one hour photo lab in 1990. I learned by trial and error how to shoot my own photos by getting them done at that lab. I was in the vert skateboarding scene, and Love Park started blowing up. Thrasher hit me up, and I started taking photos for the first article on Love Park. I think I was there from like ’92 to ’96. Then, I started working for other magazines and doing commercial photography.

Do you consider the environment in your photo compositions in addition to the subjects?

Yeah, I was always trying to make something more out of a picture. I remember this photo of Steve Caballero skating his ramp in his backyard, and in the foreground of the picture was this hammer; I always remembered that, and thought it was cool. I knew they had been recently working on the ramp. It incorporated a bit more than the skate trick into the picture.

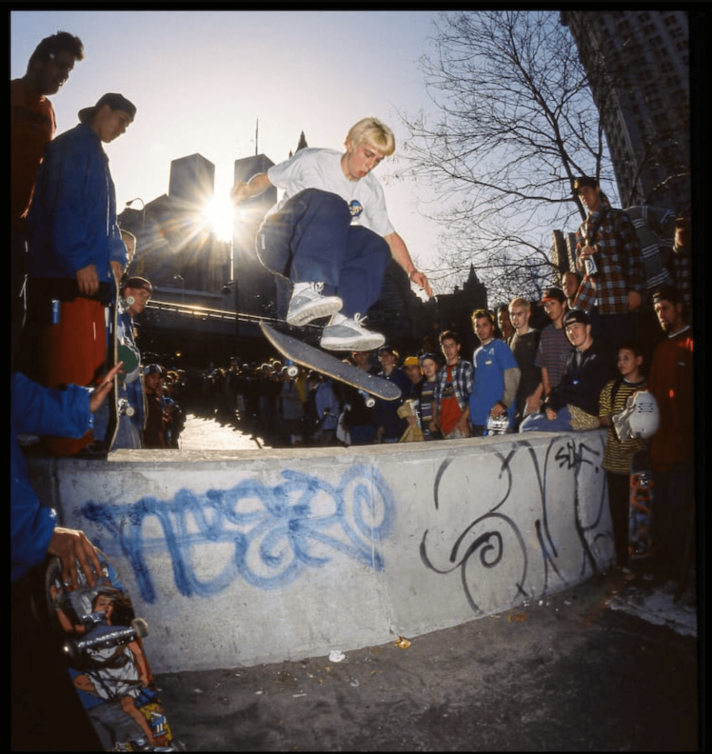

Do you remember taking that Huf picture?

You know, a bit. I remember that day, but hadn’t seen that photo in years. There was so much going on that day. I’m pretty sure I was just in the street with a flash. I must have gone up to the Banks from Philly with like four rolls of film. I saw it once, sent it to the magazine, and the last time I saw it was when it was printed in the magazine — all little and grainy. Then, I forgot about it. I’m really bad at going through my archives because if I can’t find something, I get anxious and don’t stop looking. So, I try not to even deal with it.

Around the time of #savethebanks, I was looking for photos, but couldn’t find any of the Brooklyn Banks in my archives, so I went through Thrasher‘s low-res archives and found that picture of Keith. I had forgotten taking it. I was looking at it all blurry, and I saw the Twin Towers there, and the sun coming through, and all the people, and I was like: “this is a crazy picture!”

The next day, I got a text from Mike Burnett asking me if I had those slides. I was like “What!?! I was just looking that stuff up myself. I haven’t seen them in years.” Turns out, he was working on a retrospective of the Brooklyn Banks for Thrasher. Next thing I know, he’s asking for my address, and he’s sending me a copy of the new issue with a bunch of scans of my photos in it. And they were looking crisp. They had all my slides still!

How does it feel looking back on this photo now that both Keith and the Towers are gone?

I’m a South Jersey, Philly guy. I was definitely aware of the Towers. My wife was in New York when they fell and I was calling a lot of people. All those things happened so much later than when I took the photo. I had forgotten I had taken that photo when the Towers fell. Putting it all together now, I can’t believe it. I’m really happy Keith saw it full and high res before he passed.

Bonus Interview: The Towers loom large in all American culture, not just skateboarding. They are as stark and stoic a symbol for the American Dream as can be imagined and filmmakers knew it – just watch any movie shot in New York since they were built. Here’s one such filmmaker’s thoughts….

Lloyd Kaufman

How do you use the environment you’re shooting — location and place — in your work?

Well, being a worshipper of the talents of George Romero, John G. Avelson, Samuel Fuller and others, for me, the location is more important than the stars. I have no interest in stars. The location becomes the major character.

What are some of your personal recollections of the Towers?

I was asked to testify for a hearing about New York as being a filmmaking town rather than just a location town, and I believe that was in the World Trade Center. I remember going up the elevator and it seemed like the elevators rattled along the buildings. Once, I had dinner up there with my in-laws. I remember it being all fogged in. My wife, Pat, was the New York state film commissioner for four governors; her first office was in the World Trade Center. They moved out a few years before they fell.

Much of your film-work focuses around the fictional town of Tromaville, New Jersey, which has a direct relationship to the Twin Towers. Can you tell me a bit about this?

My whole career has been based on the underdog; Tromaville is the underdog. The little town of Tromaville, New Jersey has always lived in the shadow of the big metropolis. Even going back to Squeeze Play – we would want to shoot magic hour shots from Jersey facing the big city to show its majesty and power. It’s a fond satire of a little American town.

By the time The Toxic Avenger came along, we were lucky to get some beautiful shots of the skyline of Manhattan that featured the Towers. We found a great spot that was almost like a stage, and we were able to get the camera low.

There’s a lot more of their imagery in the film. What Toxic Avenger and many Troma films address is the conspiracy that creates so-called underdogs: capitalism and money. Symbols like the Towers have the dual capacity of representing real lives, but also the powers that represent those conspiracies. How do you feel about the Towers as imagery representing what has changed since you made those films?

Well, here’s a thing – when Spiderman came out, there were all sorts of shots of the Towers in there and they erased them from the movie. [Citizen Toxie: The Toxic Avenger IV] opened two weeks after September 11th, and there was one thing I definitely wasn’t going to take out of the movie, and it was them.

My theory, which has been in all the movies, is that people can run their lives without limousine liberals or snake-oil republicans doing it for them. But, unfortunately, we have all these labor leaders who make their money off a constituency that has nothing — the federal minimum wage is what? These fuckers are stealing all they can get. That’s the bureaucratic conspiracy. And then there’s the corporate elite – I don’t have to say anything about them. They suck dry the little people of Tromaville of their spiritual and economic capital.

To see those two big blocks of cement – it’s intimidating. That real bad guys could knock them down? We never had any idea. It’s a tragic, horrible thing that happened. I’d never take them out of my films.

Previously: Unforgettable — The Oral History of the Twin Towers in Skate Photos (2019)

Thank you for this. That Harold photo at the Banks is priceless. RIP WTC

Great write up and interviews. That Qulon Douglas photo is really rad

Never noticed the towers in the Huf photo at the banks. Awesome read and amazing photos, great job as always.