Words & Images by Adam Abada

“Shut up and skate!” That is a refrain I have seen written and analyzed more than actually spoken or practiced, but its dumb ethos echoes through so much of that which is considered “real” skating.

With the mindset of getting into the “summer vibe” (or something like that), I recently watched Dogtown & Z-Boys. Sean Penn’s bitter post-Spicoli narration about the [then] worst drought in California history doesn’t specifically say “shut up and skate,” but it lays claim to the temperament that it comes from. The film made me think about skateboarding’s connection to the world: the weather, school, roads, family, class, economics, substance use, housing. The film claims modern skating was born out of a drought.

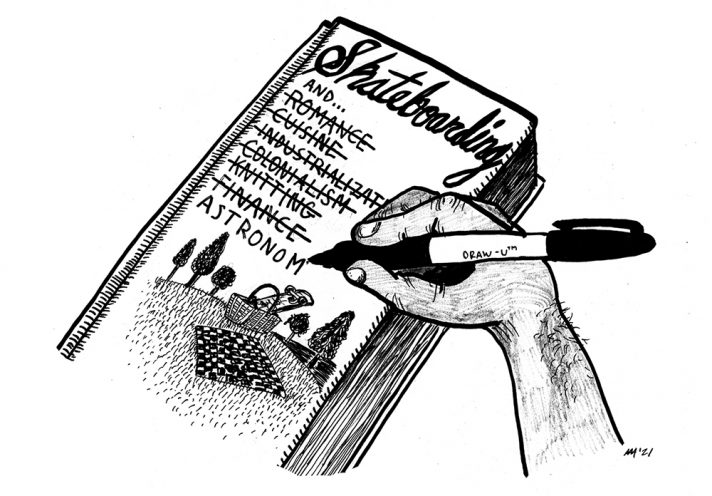

Like everything else, when we skate, we bring the outside world to it. I do want to skate, but I don’t want to shut up about it! These three authors’ — all of whom skate — books, ideas, and studies help show that we can bring whatever we please to skateboarding to make it something that pleases us.

Skateboarding and Femininity: Gender, space-making, and expressive movement by Dani Abulhawa

“Let skateboarding speak for itself,” a close relative of “shut up and skate,” seems to be applied most readily when gender comes into play. Dani Abulhawa, a senior lecturer in performance at Sheffield Hallam University, ambassador for SkatePal, and decades-long lover of skateboarding, explores this idea in her book.

Working from the vast well of existing interviews and articles on skateboarding – a technique employed by the other two books here – Abulhawa shows how just the act of skateboarding actually can’t speak for itself because it’s imbued with our identities. A lot of these identity characteristics have come to favor traditional masculine qualities. Citing examples from the 60s and 70s of girls skating alongside boys in about equal numbers, she chronicles how those gender roles changed alongside skateboarding as crews like the Z-Boys placed values on descriptors like “power,” and “raw.”

In well-researched, stated and constructed chapters, Abulhawa digs into some of the separatism in skating’s history that has influenced the culture away from feminism. She argues how the subculture leaned farther and farther towards post-feminist ideas of full inclusion and representation as it picked up mainstream steam without really allowing for any space equity.

Ideas such as bodily-kinesthetic intelligence — a theory around the understanding of body movement that allows for replicating motions — sound heady and philosophical, but make pretty damn good sense from a skateboarding perspective. The chapter on skateboarding philanthropy is informed by her role as a SkatePal ambassador. Ideas like how the open framework that many of these programs provide suggest the “strong possibility that skateboarding leads towards a development of a broad range of physical skills and self-expressions in both participants and observers” is drawn from her real-world experience.

Abulhawa describes gender as a “dialogic process occurring between people, places, and the things in a range of contexts.” Gender can be anything and skating can be anything, based on where it exists and who participates. Skateboarding culture comes from how skateboarders identify themselves, and since skateboarders participate in the world beyond itself, skateboarding cannot be defined by just skateboarding.

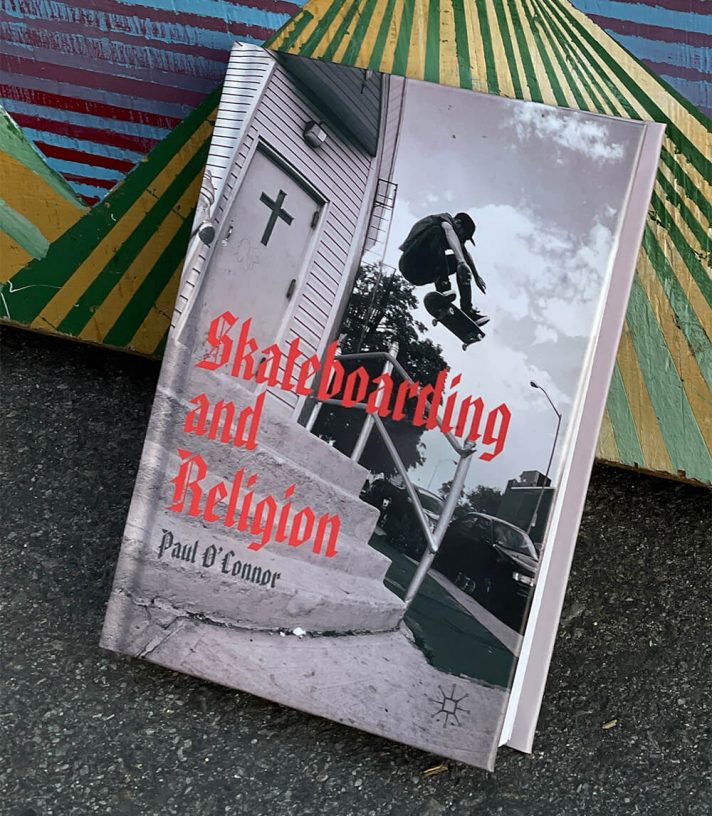

Skateboarding and Religion Dr. Paul O’Connor

With a long history of iconography, diction and prose surrounding religious representation in skateboarding, Dr. Paul O’Connor’s Skateboarding and Religion sports Zered Bassett on the cover kickflipping over a church’s bump-to-bar. Set in our vast cultural lifeworld, it is easy to see how skating can be seen as religious. This happens most overtly through graphics, music, and videos, but O’Connor’s book goes much deeper. Skateboarding and religion are both based on the beliefs and views of groups of people. They both have foundational texts and ideas. They have their legends, myths, disciples, and, even Gods. (Some of them are switch.)

Stacy Peralta rears his head yet again, with references to his origin myth of skateboarding and the idea of California as some kind of “holy land.” Throw in Peralta’s The Search For Animal Chin, infamous Natas graphics, Jamie Thomas fanaticism — the well is deep.

O’Connor brings up and balances lofty, cerebral topics like “edgework,” the voluntary taking of risks in engaging in an activity that acts as a temporary escape from societal norms; mysterium tremendum, the power of religious feeling (think the communion of video premieres); and hierophany, the manifestation of the sacred (think the hallowed ground of Love Park or South Bank), with prose getting right at the historical and emotional parts of the act of skateboarding itself.

“I believe in skateboarding scholarship,” O’Connor includes himself in his text, imbuing the value of the object in hand, “precisely because it provides a rich context by which we can understand more about society, space, and culture. Skateboarding is not a niche concern; it presents valuable lessons to us in its multiple forms.”

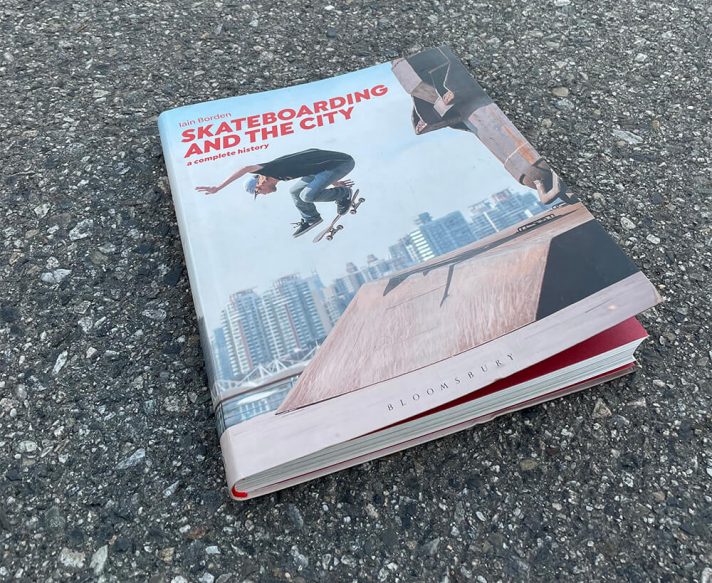

Skateboarding and the City: A Complete History by Iain Borden

Finally, the biggest book in this little wrap-up, the proper textbook, Skateboarding and the City by Iain Borden. It is a decades-in-the-making follow-up to the book that started it all, Skateboarding, Space, and the City. The latter, published in 2001, famously uses Lefebreve’s super-architectural space theory — an equally heady, thoughtful, clever, dense, and aimless French Marxist mix — to talk about the new space that is created by bodies in movement in relation to architecture. There’s some real academic weight and pedigree going on, so take that for what it’s worth. While in no way containing its totality, this book is as complete as can be in summarizing the general history, function, and equipment of skateboarding. Stocked to the brim with references, citations, video links, images, and archives, the book does hard labor as a history for skateboarding in text form that would not be out of place in a college classroom, but exists also as a jumping off-point for connecting skateboarding to any aspect of our lives.

Borden warns against neoliberalism in skating. Though touting D.I.Y. culture and wearing that influence proudly, skate culture is also subject to the same racial and socioeconomic factors as its individuals, and not everyone may be able to express this specific value. So many other identities spring out of skating. It also includes a very strong narrative identity and editorial angle that shows how skateboarding has increasingly engaged with things like “public space, historic and architectural preservation, healthy and sustainable living, and entrepreneurialism.”

Any singular skateboard mentality or history, like that posited by Dogtown and Z-Boys, seems a silly proposition when briefly mentioned in this document of skateboarding’s longevity and how it has attached it to, and been born from, many cultures outside of itself. The place from which Borden understands the history of skateboarding recognizes that a skateboard in itself, like a toy, is pretty easy to understand. It is more the complexity of its relationship to the rider, their bodies, and the space around them when things get interesting and worth investigating.

Skateboarding and Anything

There is a healthy fear in skateboarding toward the codification of its unspoken poetry into the world of intellectualized academia. Institutions certainly ain’t punk, but I’m watching the damn Olympics and I bet a lot of y’all are, too. It is still furiously hot out and there is a fan four feet away from me on full blast, reminding me that things really aren’t going to get much better unless we make it better.

When watching Dogtown & Z-Boys, I did recognize some of the 70s Venice surf style and flow as represented by Stacy Peralta in my contemporary skating. There’s truth in it. Neither his, the monoculture, the Olympic Committee’s, nor my representation of skateboarding is wrong. (Maybe the Olympic Committee’s, actually.) It is just that all of them aren’t complete and the idea that it’s not worth digging into these representations is wrong. Dani Abulhawa, Paul O’Connor, and Iain Borden help show that just the act of skating is enough to think about outside of ourselves once in a while. You don’t have to read their books to figure this stuff out, but that is not going to hurt. Neither is contributing however you want to skateboarding. Take what you love, or what makes you happy, or what feels good, and skate.

“Skateboarding is not a niche concern”

never use a ten-cent word when a five-cent one will do

‘shut up and skate’ is the only thing that matters though. I can appreciate religion and gender issues, but right now i’m at blue park big dog, i’m on my 200th try at the nollie flip out of my manual, so I don’t really care about the microagressions, i don’t wanna hear about the mets game, i don;t care your dog died. I want my trick, so please… shut up and skate. everything else is a distraction from the sole thing I came here to do.

how do you nollie flip out of a manual tho

I’m deeply disappointed that the Skateboarding and Religion book wasn’t titled “I Hope God Makes You Break Your Leg: Skateboarding and Religion”.

This is the perfect example of sloshing around high fallutin conceptual jargon to sound like, dumb smart. Skateboarding and religion: some people arent physically capable of getting out of bed, let alone walking — so doing gnarly shit and wrestling with gravity is a celebration of God’s gifts. Skateboarding and feminism? Its called style and grace something #DUMBGIRLS obv know nothing about. skateboarding and institution? If Globo Corp offers a fat bag then pay ur bills papa

would definitely read a “skateboarding and music” book that chronicles all the music scenes and affiliations that have sprouted alongside skating’s history.

Great write up — though not a little dispiriting that the remarks above constitute a miniature case study unto themselves: Skateboarding and Myopia.

shea, academics/journalists who write articles/books like the ones above are parasites. they contribute nothing of worth to skateboarding! they only participate in and publish about subcultures to gild their own reputations. subcultures that let them in are diluted and then destroyed entirely. it is not “myopic” to abhor parasites. it is a sign of subcultural health.

now shut up and skate.

@stan yelants pretty certain every author in this article was a skateboarder long before they became an academic – not that the two are mutually exclusive anyway.

Anyway, Dani has worked with SkatePal and Iain Borden has been involved with various efforts to create/maintain public skate-spaces. To say “they only participate in and publish about subcultures to gild their own reputations” is beyond misinformed.

hi FG

“every author in this article was a skateboarder long before they became an academic” shame on them for selling out and trying to turn their participation in something beautiful into tenure.

“dani has worked with skatepal” oh wow she helped give skateboards to a bunch of kids living in a war zone

so thoughtful and helpful

i’m sure when the IDF gets around to bulldozing their homes they’ll be overjoyed to have been given a skateboard back in the day, definitely real/valuable/helpful charity work and not a way for westerners to polish their resumes/signal their virtue to other westerners like i was saying.

“various efforts to create/maintain public skate-spaces” ah yes the “public skate-spaces” that exist to confine an inherently rebellious activity. “you have a park to skate, why are you skating Here?” i’m not going to claim they’re all bad but they’re pretty clearly part of the larger neoliberal project to confine/sanitize/commodify rebellion, dude’s an academic so i’m sure he’d be able to grasp that if he wasn’t busy using his participation in those efforts to burnish his reputation.

Academics by its nature is parasitical. Its colonization of thought. Thats how you publish books, make tenure, and finally eke out a living wage in the game. Not to mention predatory of young kids who make federally-funded, life-marring mistakes in “studying” the humanities. The write ups above are all circular insipid drivel, maybe indicative of a larger problem in the humanities, which has turned its back on demanding well formed theses in favor of just taking kids money and letting them write whatever so long as its not remotely conservative

Oh my god please take this scorched earth edge lord shit back to the fucking slap boards you virgins.

Huh?

in my humble opinion, some of y’all got it all wrong with ‘academia.’ it’s like literally everything else in this world: there are posers, there are kooks, there are people who do it for the underage women, there are some who step on everyone to get to the top, there are people who think they know-it-all and don’t, there are people who try to cram their ideas down your throat. on top of that, it’s corrupt and run by $$$.

just like hmmmm, let me see, skateboarding? you realize all those companies you buy skate products from are, well, companies? and that by their nature companies exploit the people that work for them to make money? you know skateboarding is now in the olympics, which is run by one of the most corrupt organizations in the world? you know there are big budget tv shows and movies about skateboarding?

yet, just like skateboarding, you can wade past all the bullshit and find real ones—people who just do it for the love of the game. and at the end of the day, there’s really not much difference between nerding out on descartes and nerding out on skate content. it’s a similar level of obsession that goes into to figuring out what plato meant by ‘justice’ as trying to land your next trick.

(and none of this is an endorsement of any of these, more than likely, over-priced books, which as someone with a stake in both looks like the worst of both worlds)

Nerding out to Descartes and skateboarding are similar in that you can do them both on your own time for cheap. You can spend $160k to study Descartes if you want, its your money and your future. Skaters dont take out mortgage money for the privilege of being sponsored. If a skater feels “exploited” then they can shop sponsors and let the market determine how underpaid they are. That skater doesn’t owe $1000/mo for 10-15 years to that should be a RICO charge

Just go push wood. That nerd stuff is for the birds. Save da money buy a vx1000. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Hahaha thank you, this banter made my day.