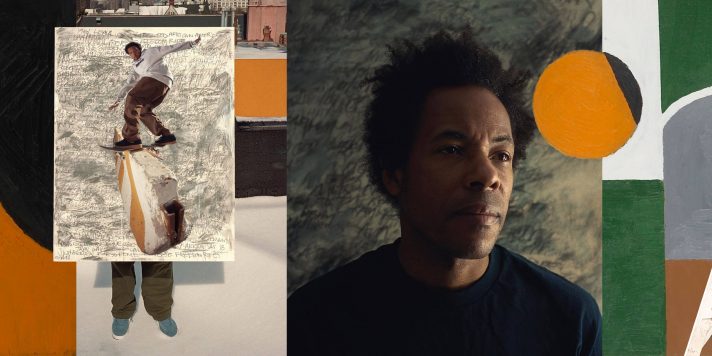

Intro & Interview by Adam Abada

Collages by Requiem For A Screen

Original Photos by Cole Giordano & Pep Kim

Jahmal Williams is as humble as he is effortlessly flowing on his skateboard. He is someone with thoughtful personal aesthetics that you could never mistake for pretension. That translates into his effects on skate culture — one that he has been a part of for many decades now. A painter, sculptor and connoisseur of 180 nosegrinds, Jahmal is also a father and runs his own cult favorite brand, Hopps.

“Keep It Moving” isn’t only Hopps’ slogan, but a philosophy that keeps Jahmal relevant and creating great work. With a mind and personal history that exemplifies striking while the iron is hot, Jahmal’s new mural and accompanying short is the type of pandemic-era work that reveals how constantly evolving he is.

I’m glad we waited until the “Dreamer” film came out before we talked, because it directly relates to a lot of the work you’ve been creating. Can you tell me a bit about that project?

Pep [Kim, who directed “Dreamer” with Jahmal] and I have been friends for quite some time. We like to enjoy the sessions and document things as the fun is happening. I got an opportunity to do a project with Converse that was about celebrating black joy and I ran it by Pep. He came by to shoot photos of the artwork, I started explaining the subject matter, and we started vibing on the topic.

Converse ended up presenting another project to me, so I tied the work from the first project with Pep into this one. I was investigating my family history as part of this thing called the “Reverse Freedom Rides.”

What are the Reverse Freedom Rides?

Around 1961, there was an event called the “Freedom Rides,” in which civil rights activists rode interstate buses into segregated southern states to protest Jim Crow laws. After, in 1962, there were a bunch of white southern segregationists from around Arkansas who wanted to play a political game of retaliation against northern liberals, and they bussed poor African American families from the south up to the north.

My grandmother and my mother were one of the families who these segregationists bought one-way tickets for — to Hyannis, Massachusetts. They told my grandmother that the Kennedy family and the President were going to be there waiting to receive them, and that they were going to be presented with housing, good jobs and all these great opportunities. When they got to Hyannis, of course, it wasn’t like that. No one knew they were coming. It was this big political incident that happened.

A journalist from NPR reached out to me and my mother — that’s how the history came to me — maybe a couple of years ago. The reporter was doing a story on the Reverse Freedom Riders and was presenting to my mother and myself. We were blown away. We had never known of this documentation of the events.

She found you?

Yeah, because my mother is one of the few people alive that has been through that experience. I’ve been investigating the story since. When the Black Joy project came up, I wanted to give my grandmother some props and I wanted the artwork to be centered somewhat around her and my mother. That’s when I knew that I had to dive back into this story. I listened to the NPR piece, and I was reading as much as I could while I was producing the paintings. It was part of a process of ingesting the information, listening to the stories, looking at photographs and allowing that stuff to come out spontaneously on a canvas.

That’s serious family history to be learning at this point in life. Are you using artwork to process some of that understanding?

Yeah. That’s a part of my catalyst. Artists often have problems finding meaning in their work, and right away, that was something I knew I wanted to dive into. It was a great opportunity to do some introspection and learn about my family history. I gained some understanding of how my life and upbringing has been the way it was.

That’s how the “Dreamer” project came up, in a roundabout way. The first thing I produced on the topic was a series of three paintings on the Reverse Freedom Rides. The idea is that I couldn’t do what I do now without the sacrifices that my grandmother and my mother made in the past. It’s a way of me finding my position now and being appreciative of what they did in order for me to be able to dream, be a skater, to pursue a career in the arts, and so on.

It’s cool, from a skateboarding perspective, that you’re such a northeast guy. That’s a really interesting history of how you got there.

I always wondered how my family got to Boston. I grew up in the Jamaica Plain Housing projects too, so after I started getting older, I was wondering how we got there. I would hear stories about the south and my mother growing up raising animals on their farm, but I could never really understand it because I was growing up in the city. It was kind of hush-hush for a while, and then my mother would tell me that we were “freedom riders,” and I was like “really?” And then it turned out we weren’t freedom riders — it was a reverse freedom ride. The story turned to that. At my grandmother’s funeral, the topic came up again.

In the end, there is a sense of freedom.

Yeah! When I’m producing work — even designing things for Hopps — I’m looking for things that make sense to me. Actually, the “Dreamer” piece was a composition that I had done previously. It had to do with flow and transition. It was actually done at one point as a skateboard graphic. I painted it on a skateboard at first. Then, I painted it as a triptych. Then, I painted it again on a canvas board. There were a lot of different processes that I went through with that piece.

All of these things started connecting into the “Dreamer” stuff. The mural was for Pilgrim Surf and Converse. I had that wall and I had to see how I was going to approach it. This whole year, the idea is that when I produce stuff, I’m going to always be revisiting this narrative, investigating my story, and seeing what comes with it.

Have you done a mural before?

I have a history of writing graffiti and tagging, but I can’t say that I’m a muralist.

I’ve associated you and your skating with bricks over the years. From Copley, to this mural, to other spots. It seems like you have a fine attunement to textures, as a skater and an artist.

It’s been a constant throughout my life. I’m sensitive to it. A friend of mine, Matt O’Brien, even gave me one of the bricks from the Boston City Hospital banks as a present. Concrete, asphalt, bricks, the ground — all those sensitivities towards material, rocks and surface — skaters have that like a mason. I do sculpture work and I have yet to work with stone, but it’s something that I’ve been wanting to do for years.

And you know what that is? That’s the environment. That’s the northeast. Sometimes you end up becoming a — I don’t want to say product of your environment — but it becomes a part of you. You start speaking that language and understanding it in different ways.

I’m less interested in if skateboarding can be art or if art can be in skateboarding, but how do you think the two disciplines — if you consider them that — inform each other?

I was studying at the Museum of Fine Arts under a professor by the name of Milton Derr. I never told anyone in art school that I was a pro skater. I didn’t want anyone to know because I didn’t want it to be a distraction from my studies.

One semester, I didn’t do so well, and I finally told some of the faculty that I wasn’t producing a lot of work because I was traveling the world skateboarding. And they were like “What!?!” Milton Derr, my other professors and my guidance counsellor, Stanley Pickney, started telling me things about my work that I didn’t know. Stanley was telling me he saw sculpture in my drawings and paintings, and that I had a three-dimensional perception on flat surfaces. They pushed the button and asked why I didn’t incorporate more of my skateboarding into my art. They told me that I should embrace it and inform the two processes with each other. That’s when I started painting on boards or using the board as another vehicle to do sculpture. I started thinking about flow and the feeling of skateboarding — like the feeling of “pop” into my work.

How do you keep that conversation fresh and exciting in a way that helps you produce new work — both in art and skateboarding?

Over the years, in hindsight, I’ve learned that it’s a daily practice. When I’m skating my best, is when it’s a daily practice. Something that I’m living and breathing every day over and over. It has to become second nature. It’s the same with art. I feel like my work is the strongest when I do it every day. I don’t actually skate or paint every day at the moment, but in order for me to be in tune with those practices, it needs to be a discipline. That’s why I look at skating as an art form and art the way I do.

It’s interesting to see how it was people from the art part of your life who told you to bring skateboarding into art rather than the other way around.

I thought it was corny! I didn’t have an art education yet, and my peers were graffiti writers and street artists. I felt like I had to keep it real. Skating is one lane and art is in another. When it was brought to my attention, I opened my mind a bit and saw how they could inform each other through practice. I had an extremely positive experience in art school.

As a skateboarder, what made you decide to go back to school and study art in a serious manner?

I wasn’t making too much noise in skating at the time. I wasn’t sponsored; I was going through some growing pains. I remember I was at a buddy of mine’s place, and I would sit there and draw sketches while we were waiting to go skate. He would collect my drawings and tell me I needed to do something with them. I didn’t have the belief in myself that I could do much with my art.

There was another thing that happened. This is really personal, actually. I had an uncle named the Drummer Man. When I got into jazz music, I wanted him to teach me how to play drums, but he soon became very ill. It turned out that he was dealing with a brain tumor. I would go to the hospital and spend time with him, wash him up, hang out and talk. He started telling me things before he slipped into a coma. One of the things he told me to do was to go back to school. As hard as it was to see him in that shape, he was telling me things before he passed that really made an impact on me and gave me some direction in life. That was also a part of the motivation when I was going through my personal renaissance.

I believe it was 1998. My mother gave me a lot of support and encouraged me not to waste what she called a God given gift, my art. I applied to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and they asked for a portfolio, which I didn’t have. They gave me six months to put one together and I just honed in. At this time, I was going through a transformation. I had discovered jazz music; I had been reading a lot and making art. I got my portfolio together and I ended up getting accepted. The admissions office said it was one of the strongest portfolios that they had seen in a long time and I ended up getting a scholarship for four years to study art at the SMFA Boston.

You could have been a jazz man?

When my uncle passed, I met another teacher — ironically on the street corner — who happened to be an older jazz musician. His name was Billy Skinner A.K.A. King Cat from Buffalo, New York. I wanted to play drums, but he wanted me to live and breathe trumpet, so I started playing the trumpet with him. This was around the same time I got into art school. And all of a sudden, I got on Adidas and they wanted to sign me as a pro rider. All this stuff came back around. Things started happening for me with skateboarding and art. The problem was I couldn’t do it all at the same time. I couldn’t turn down this four-year scholarship or this Adidas contract. I wanted to pursue music, study art, skate and travel. Eventually, I would let go of the trumpet.

It sounds like you’re good at listening to your history and intuition. In telling me about your family’s story coming to Massachusetts, I see that direct link to where you are now.

Yeah! You see how the stories connect? It’s hard to put into words, but I just have to listen to it and follow it.

How do you keep it so diverse and forward-thinking? You also have kids and run Hopps, of course. And there’s a pandemic.

I guess — I have a burning desire.

A burning desire for what?

For the stoke! I love being stoked. I can’t get stoked out on too many things other than skating. That feeling — I want to keep getting that as long as I can. I try to stay mentally and physically healthy, number one. I started going to a Buddhist meditation center up on 23rd Street for the past four years or so. Once the pandemic kicked in, I started doing online sessions. I got more into that to keep myself balanced. You can burn out and get stressed out. Having that mental balance and being able to regulate yourself helps. I want to be physically able to skate and do the things that I love, so I try to eat healthy, stretch and do the things I got to do to stay limber. Keep everything in moderation.

Keep up with what Jahmal and Hopps have going on via @hoppsskateboarding on IG.

That was an amazing interview, thank you! Jahmal’s art is always fresh and inspiring. It was cool to get a glimpse of his work process and what drives him.

Jahmal #1 King . #1 Hero . # 1

That was an incredible interview, introspective and educational. I love the new mural. Always stoked on Jahmal’s skating and Hopps.

Hopps should sell prints of Jamals work!

@Jamal For president, Jamal is the founder of Hopps… r u out of the loops or somethin

Jahmal is an amazing young man!!!

We concur Mrs.Williams! He turned out alright!

;-)

Yooooooo!!!!! This was excellent. Definitely wish it were longer, but any Jamal is always good Jamal. I’m kinda feelin like he’s an East Coast counterpart Ray Barber, in a way. The positivity. The innovation. The art. The longevity.

I’ve been stoked on Hopps since day one & I can’t be happier that it’s still going strong.

Thanks, Snacks. Glad to see this!

Super dope. Jahmal has always been an inspiration. Dope to see him still going hard.