Words by Frozen in Carbonite

Poster Design by Order

I think it says in that book The War of Art that just sitting down and doing the thing can break down a creative block. Sometimes, a project takes on a life of its own and becomes something you never imagined. Skate videographer, Jeremy Elkin — whom you might remember from Poisonous Products and The Brodies — initially set out to make a documentary about the seminal Zoo York video, Mixtape. His research led in a more expansive direction.

More than once.

“You can’t make a Mixtape documentary without the rappers. So that went haywire.”

The project evolved into more of a quasi-autobiography of Zoo mastermind, Eli Morgan Gesner, with whom Elkin linked when he moved into the same neighborhood. After hearing tales of the late eighties and early nineties scene in downtown New York, the idea of a story began germinating in Elkin’s mind, with Gesner’s diamond mine of archival footage functioning as main source material.

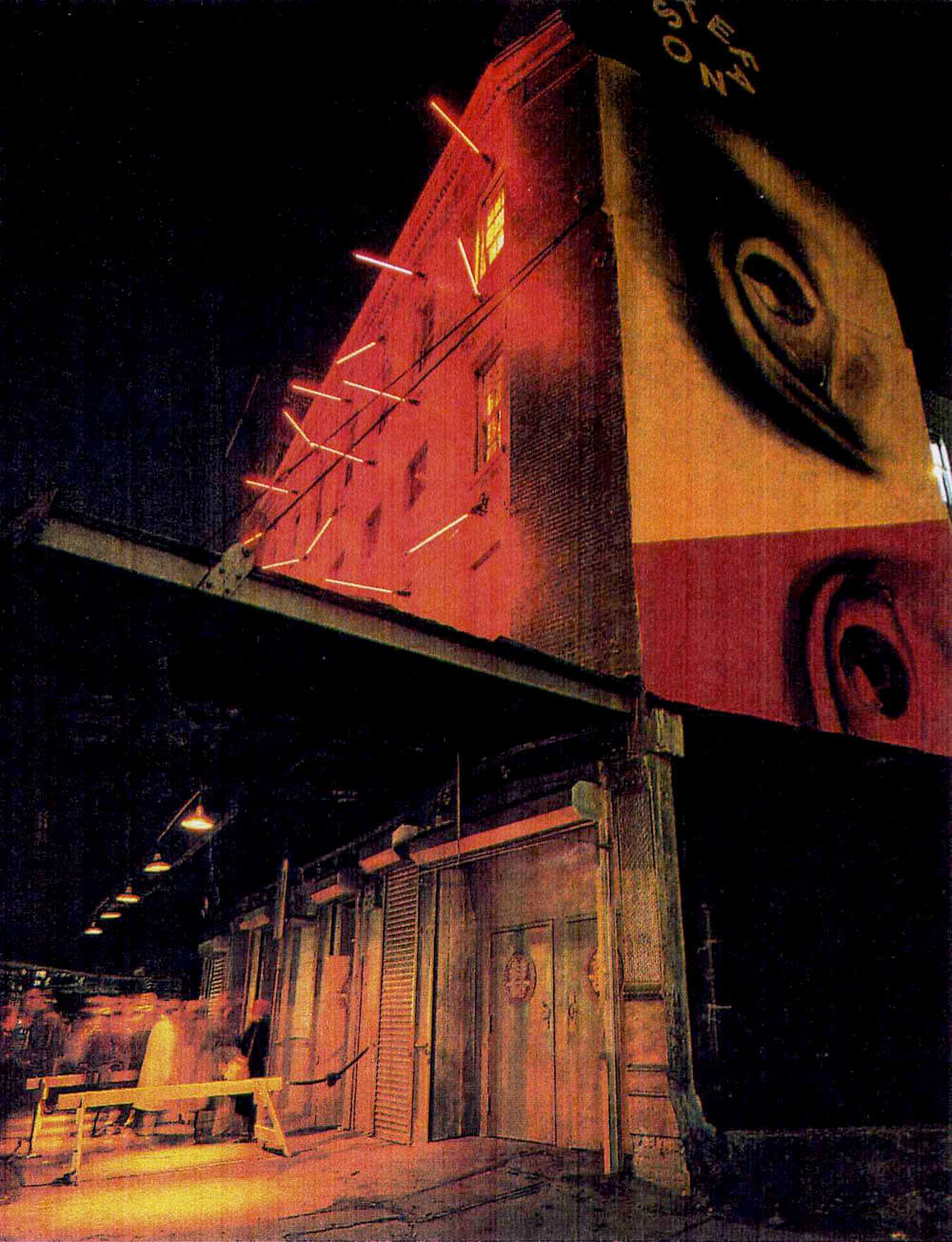

As it happens, Gesner got his start in the working world promoting parties at the Meatpacking District club, MARS in the early nineties.

“At the end of three months, I knew every single bouncer, every door person, all the party promoters,” Gesner recalled.

When MARS management offered him his own party in the basement, he convinced them to let him start downtown’s first hip-hop weekly. As is the case with skaters to this day, they partied where their bros work. Based on current data, this means that MARS was the first “skater bar” in the history of Planet Earth.

Photo Courtesy of Yuki Watanabe

At this point in the story, the narrative changed again. “Interviewing [MARS manager] Yuki Watanabe changed the film completely,” says Elkin, because he shot 30-40% of the archival footage in All the Streets Are Silent. “A lot of the things we talk about in the film don’t exist online.” Rap (in the context of The Club) and skateboarding culture functioned on the outskirts of society in the pre-social media era. In addition, Gesner — along with Jeff Pang and Vinny Ponte — facilitated even more interview sources, including the renowned cultural critic, Carlo McCormick and Rosario Dawson.

Watanabe’s archival club footage of MARS established it as the locus of the convergence of skating and hip-hop with Gesner at its center. Indeed, for nightlife enthusiasts or cultural completists, the club footage is worth the price of admission alone. Today, it may as well be from an alternate universe.

Until Riverside Park opened in 1995, skateparks in New York City did not exist. Along the same lines, there are no “rap parks” with MacBooks and SM58s and shit for people to freely make music.

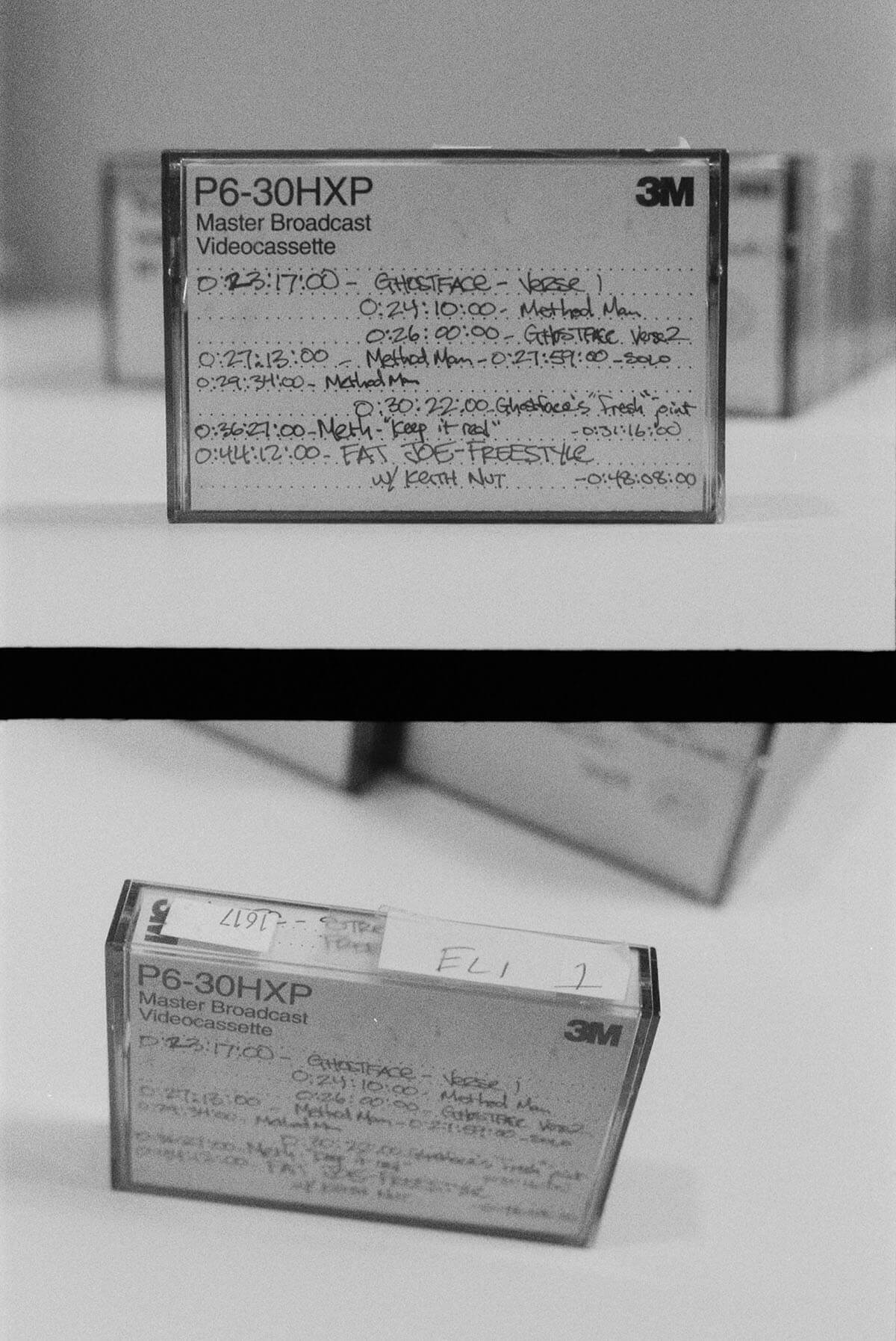

The closest thing was The Stretch and Bobbito Show on Columbia University’s WKCR.

Photo by Zander Taketomo

Beginning at 1 A.M. on Thursday night / Friday morning, (the perfect time for “mellowing-out” after skateboarding), the show functioned as theatre of the mind and a window into a different world — kind of like if the World park had a live Pay-Per-View or whatever. Taping the show on an Aiwa boom box became a ritual, but Gesner had the foresight to bring a video camera up there to document the legendary performances — material that later formed the core of the #musicsupervision in Mixtape.

“What was it like running a small hard goods company on the east coast at the time?”

“Impossible.”

That is how Gesner describes launching Zoo York, which the film also details with archival footage and ads. Just as he did with MARS, Gesner filled the void left by the demise of Shut with a new brand, collaborating with Shut alum Rodney Smith, who fabricated the board presses with Gregg Chapman on Long Island.

“It was all very arts-and-crafts,” Gesner said. With reference to Zoo’s celebrated art direction, he cites “old municipal buildings, vibes of decay, futuristic font usage, marble textures, run-down subway grime” as his main influences. He also emphasizes the availability of his own personal color printer (which he convinced Russell Simmons to buy him during his stint at Phat Farm) and a scanner as critical tools in creating that signature aesthetic. Even before those ads, though, the first black and white Zoo ads in the back of Thrasher with the handstyle logo hit hard as fuck.

Photo by Gunars Elmuts

Silent delves into the primary gathering places of the culture — the Banks (very intimidating), the genesis of Supreme, and Astor Place, A.K.A. “The Cube,” which was a fantastic place to buy lightly used product or find out where parties were and shit. Since it has been redeveloped in that weird designed-to-be-unskatable way that most new architecture in the city has, I will explain the spot as such: A triangle in the middle of the intersection of three streets where people skate flat in as if there are no cars coming.

Like most skate videos, the Zoo video was rumored to be in the works for years. There had been hints before — Andy Howell with the New Deal graphics and the live-on-tape DJ mix that soundtracked the classic Skypager video — but Mixtape stands out as the first fully actualized document of the two cultures vibing together. Shoutout Henry Sanchez and Pat Washington’s part in the Gold video.

In the film, Mike Carroll offers an on-screen realization that while the artists he was listening to in the nineties felt worlds apart from his existence, their approaches and current-day statures are not much different than skaters of the same era. One could say skateboarding and hip-hop meshed so well because they both consisted of friends doing creative shit they like to do just because. Not for the money or recognition, but yes — “for the culture.”

Photo by Gunars Elmuts

When asked about the current group of New York-based brands, Elkin says, “It is just different groups of friends who make product. People get psyched on the closeness of these friend groups and the ways that they’re branding. It’s all crew-based.”

Towards the end of the film, Elkin draws parallels between rap and skating blowing up. In 1990, Guns ‘n Roses and C&C Music Factory were popular as fuck; rap has been the dominant genre in the world for ten years or some shit now. Kids, for better or worse, illustrated an interpretation of the skate lifestyle to a worldwide audience. Today, skating is in the Olympics.

Elkin leaves the viewer with food for thought on the value or pitfalls of “blowing up” against a backdrop of the modern-day New York. Is culture always destined to become merely another form of capital? These are tough questions that are interesting to think about. As for the All the Streets Are Silent‘s final form? It is what it became: cultural document, case study in entrepreneurism, gold for skate nerd completists, and an instructional video on finding one’s lane.

As I was working on this article, my son (who listens to rap but does not skate) asked me whom I interviewed.

“Oh, a bunch of people, like this guy that runs this skate company Zoo York.”

“Zoo York? Lil Tjay has a song called ‘Zoo York.'”

Circles bro. Life moves in fucking circles.

The filmmakers are hoping to release All the Streets Are Silent before the end of the year.

What an awesome article, cant wait for the film to come out — NY in the 90s/early 00s was so different — rents were cheap, u could cop fat beef n broccoli staple dubs at a bodega, and all the new hot music was right there at the mixtape spot — back when French Montana was the smack dvd filmer

I cant wait for this film, there is nothing like NYC skateboarding! And the 90’s area seems almost lost or undocumented.

Very excited for this. Love Elkins filming… there’s no way this won’t be amazing.

early ZOO Ads were kinda the best thing ever . . .