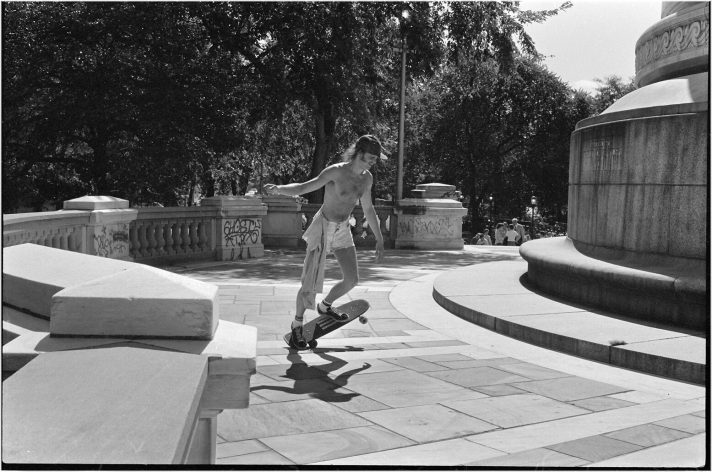

Soldiers & Sailors Monument, 1979. Photo by Nathan Tweti

Intro & Interview By Tom Ianelli

Photos by Greg Navarro, Daniel Weiss & Matt Weber

When a kid first picks up a board, their perspective on skating is inherently limited. It is a moment in which all skating is usually represented by the neighborhood spot — be it a driveway, parking lot, or skatepark — and the people found at that spot. The years pass, and skate culture opens up as one watches videos and travels further away from home, but there is a purity to that initial perspective, when skating, and one’s burgeoning love for it, is narrowly embodied by that singular spot.

Filmed entirely at the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Greg Navarro’s “The Upper West Side Curb Club,” is a skate filmer’s loving tribute to the spot he grew up skating.

Rarely seen in videos, the Soldiers and Sailors Monument, or just “The Monument,” is made up of a few curbs, canons and some “ledges,” that are tucked up in a park on 87th and Riverside, secluded from the shinier skate hubs of New York. With a cast of locals hitting every inch of the park, making spots out of the crust available, Greg’s video is reminiscent of simpler days spent trying to find new possibility in obstacles that have already taught you everything you know about skating. “Upper West Side Curb Club” is not limited by this nostalgic simplicity: the video is evidence that a spot’s value is determined primarily by the devotion and creativity of the skaters who hang out there.

I sat down with Greg at the new Andy Kessler skatepark on 108 to talk about the video and The Monument.

Are you originally from the Upper West Side?

I was born and raised on the Upper West Side. I lived here my whole life, on Broadway.

What was your first memory of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument?

When I was maybe five or six, I went there with my mother one day. The Monument was all gravel back then. They’ve torn it up and changed it so many times, but I remember I took my mountain bike there and would try to jump all the cracks in the ground, or if there were any cobblestones leftover, I would bump off of them.

When you first got a skateboard, was the Monument your first spot?

Yeah. When I got to kindergarten, my friend Dean used to skate with his older brother and his friends at the Monument after school. I just thought, “These are the cool kids, I want to know how to skate so bad,” so I begged my mom for a board. I got one at the toy store — like a really bad one with a blue lizard on it. I think it came in plastic wrap. But I still took it to the Monument immediately. It was gravel back then, you could only skate the very top where there’s a small manny pad and that’s it.

But yeah, I used to skate with my friend Dean, his brother Thomas, Patrick Morales and Hakeem Lewis. Patrick and Hakeem are actually, or were, in RatKing, better known as Wiki and Hak.

Yeah, I know them.

I still talk to Patrick all the time. I helped shoot one of his music videos with Skepta. hen I think of my earliest memories of Monument, it’s with Patrick and Dean.

Is he still skating?

I’m sure he still skates, probably has a cruiser board.

I know the namesake of Terminal Skate Shop is a little curb spot at the George Washington Bridge Bus Terminal that’s not there anymore. What’s with people living uptown and fetishizing these crummy spots?

In Manhattan, once you get above like Midtown, the skate spots start to dwindle, and it becomes a lot more residential. There’s less plazas, fewer neighborhood parks, there’s a lot less open space. The grid becomes a lot more prominent, so the spots are slim pickings.

But for Terminal’s sake, I never got to skate it, but there was a whole community of people skating this one perfect curb. I think it was metal, like one long metal curb at the bus station. Eugene, who owns Terminal, could probably talk about it forever. They’ve opened up a skate park at 181st Street probably because there were so many kids skating at that terminal. But I don’t think that there’s a fascination with curb spots. What it is, is that there are just no real spots.

What’s funny is that’s how most people who don’t live in dense hubs like New York or Los Angeles have to fare: with no spots. Especially as a young kid, when you aren’t as mobile…

That’s how it feels like when you’re uptown. As soon as I got old enough to take the train, my friends and I were going downtown because it’s so easy and the spots are in all the magazines.

When did you meet Miles [Cohoe]?

Miles was friends with all the kids my age that lived nearby. I met them when I was around 12-years-old. Once they fixed the Monument and put those hexagonal tiles in the ground, we all started hanging out there and started waxing the two-stair.

When it was gravel, 2007. Photo by Daniel Weiss

Miles has a big part in the video, and I know he’s from the Upper West Side. What was it like filming with him after having skated the spot for so long?

I always thought he was great skater because I could never skate as well as him, and I mean, everything he’s learned on a skateboard, he learned at the Monument. I knew if I was going to make a Monument video, it had to have Miles in it.

There were some struggles because I had to convince him to skate parts of the spot that he didn’t think he could skate, like the benches. But also, we had skated that spot for so long, it was like, ridiculous and redundant filming a part there. It was me trying to tell Miles to re-skate something that he’s been skating forever, and sometimes, we want to go skate somewhere else. But I’m really glad that he was able to film basically a whole part there.

Yeah, he’s a modest guy, but he’s so smooth.

Yeah, and he doesn’t want any shine, even me talking about him right now is too much.

So I hear kids talking about Monument as a real spot now after the video.

Whoa, really?

The kids are talking. It’s going to be a destination uptown.

When there was talk of Thrasher putting it out, my friends Zack, Wes, Miles and I joked around that it could ruin the spot — like who knows, it could even get so bad to where it could shut down or get knobbed. It was our local spot, and it was so rare to ever see anyone come around who wasn’t from the neighborhood because it doesn’t feel like a place you would want to go skate on purpose. Once you go there, there’s nothing else. But if people want to come skate this spot and try their wits at sessioning a one-inch-tall curb with cracks and stuff, please, have at it, be my guest. It shouldn’t ever be about colonizing anything. It should be about visiting and enjoying whatever is there, you know, the fruits of Manhattan architecture. But then, obviously, paying respect to whoever was there before you. There were generations of people that skated the monument before me back in the 80s like, Andy Kessler and Eli Gesner.

In the video, you paint a concise picture of the Upper West Side with the non-skate images of the Monument and neighborhood. I was wondering if you had a vision going in, or if that style just became appropriate with the footage you ended up with?

The monument itself, once you go there — especially in the summertime — you just stare at this thing from afar. When the Monument was built in 1902, the Upper West Side was predominantly two-or-three-story mansions, so it was a tall structure for its time, and it’s just a really gorgeous thing. If you look at it, there’s nothing obstructing it. It just has a very photogenic lure that I really wanted to capture. It’s traditional to have B-roll shots of whatever the surroundings are amidst skate clips, so I tried to capture the Monument. It was intentional. I’m trained as a filmmaker and photographer, so I started storyboarding and stuff.

I think I met you a few days before you premiered it at 108. You told me that it was your first video and I didn’t believe it.

That wasn’t my first video. I’ve made videos before that weren’t skate related, like narratives with my friends for school or whatever. I’ve also made really shitty Facebook skate edits with my friends that were nothing crazy. But yeah, never had I sat down and been like: “I’m going to make a real skate video.”

The sound design in the vid is smooth, but if you pay attention, it’s detailed the way you layer it. How much labor did that take?

Over the years I’ve been fascinated by Foley art, which I feel like is an under-appreciated section of filmmaking. When you think of Foley art, you think of Hollywood films. You don’t think of Foley art with skate videos.

But when Ted Barrow told me he didn’t want music, I had to start thinking about the sound, because I didn’t want it to feel like a rough cut. I wanted it to feel immersive, so people didn’t get bored; I wanted it to feel like a movie. In terms of labor, there were three days where I went out to Riverside Park with my audio recorder and recorded every sound I could — the wind, the flagpole, the ground — and then I’d go back home and mix it in the timeline to fit Ted’s skateboarding. It was meticulous, you know, and I still feel like I didn’t get it right, but I’m glad that nobody notices.

In the video, the footage is of the locals like Miles and Ted, but then there’s huge names like Mark Suciu and Frankie Spears. What was it like to have more established guys come skate and be in the video?

A lot of that was thanks to Ted Barrow. I had to strike a balance between it being my video, Ted Barrow’s video, and then just an overall skate video. In order for it to get any sort of traction, I definitely wanted to have some bigger skaters that people would know globally, even if that extended beyond my friends. But really, I just wanted to see if other people could skate this spot, to see if it could be bigger than just us. There were a bunch of pros I talked to that couldn’t make it uptown, or just said no. But the established dudes who did come — like Mark and Frankie, Elijah [Cole], Yaje [Popson] and Taylor [Nawrocki] — are all my new friends now. It didn’t feel forced. They genuinely wanted to be in a Barrow production, and, for me, it was a dream come true.

If you’re going to be a skate filmer, you want to capture really great skateboarders and I grew up watching Yaje, I grew up watching Mark. And then there’s a ton of skaters in it beyond Upper West Side locals, besides the professionals: people like my friends Mecca [Mshaka Morris], Kai [Roper], Cooper Winterson. I look up to those people as other great New York skateboarders that I was really proud to have in the video.

Ted Barrow. Photo by Greg Navarro

Do you enjoy one spot parts? Did any come to mind when you started wanting to do this?

I’m inspired by concept videos, like Colin Read’s videos, Tengu: God of Mischief or Spirit Quest. All his videos were memorable. I just knew I didn’t want to make another downtown skate video. I wanted to keep it local and, knowing that no one’s ever done a video in the Upper West Side, I was way more motivated to make and edit my own video. But yeah, when “Hometown Turf Killer” came out, that part blew my mind. The fact that Bobby Worrest loves his local spot so much is the coolest thing. He did almost everything you could think was possible there and I loved that. All the Brian Panebianco Sabotage videos too — those inspired me as a kid.

I liked the Andy Kessler bit at the end, partly because it felt like it brought the focus back to the history of the spot and its placement in the city. What’s your impression of Andy Kessler and his being from the neighborhood?

Yeah, I don’t remember how old I was, but we tried to go shoot down that big hill — the suicide hill on 91st Street and Riverside Drive. Somebody had told me — it might have been my friend Matt Weber — that someone had bombed the whole thing. Then on YouTube, I found a clip of Andy Kessler in Deathbowl to Downtown by Six Stair, of him just shooting down that thing. It was so crusty back in the day. That always inspired me. But once I found out about Andy, he had already passed away. It was after he died that I found out that he built the Riverside skatepark on 108. He was an early member of the Soul Artists of Zoo York. He was just the O.G. east coast skater plain and simple.

I hope that including him in the video was some skate history for kids because, you know, they might not be up here skating if it wasn’t for him.

The video was on Thrasher, which means it was seen globally, but it’s just your local spot. What do you hope people get out of it?

After the video dropped, I was getting like a flood of messages and emails from people across the world. Some people said it made them feel grateful about their friends and their local spots, and some said it made them want to get out and go skate their local curb, which is all I really dreamt of. I didn’t want to make any money. I just hoped that the skate video I made inspires people to go skate, or visit somewhere that they haven’t been. But really, just go do things with your friends and go skate your local spot. They’re the best people you have. It’s the best spot you got.

Well, that’s all I had written down. Do you want to shout anybody out?

Shout out to Andy Kessler. Yeah. Miles Cohoe. Ted Barrow for helping put this whole thing together and co-producing it. My one patron is Sarah de Luna. She reached out after just having watched the trailer, so I would like to give her some credit. She’s a very sweet woman that lives in Whittier, Califronia. I never met her, she doesn’t skate, but she helped me fund the project.

Thank you to everybody who helped produce a custom score for my video. I can’t even name everyone.

Thank you to my mother, who passed away five years ago, for taking me to the monument every day to ride my bike.

Support the Upper West Side Curb Club by getting the DVD, stickers and postcards on the U.W.S.C.C. webstore ♥

what is the lat/long of this curb spot

Writers: “The Monument,” is made up of a few curbs, canons and some “ledges,” that are tucked up in a park on 87th and Riverside,

Skaters: where is this spot?