If the act of skateboarding is a universal language, then does a skateboarder need to know how to speak, let alone decipher the meaning of text? – Inquisitive Gentleman

I now leave to the magazines, to the growing number of documentaries, blogs and the internet in general, the task of completing and filling out the gaps in this project. – Raphaël Zarka

Review by Galen Dekemper

The methods of product presentation and transmission are important in a multimedia age. In 2011 one can easily curate a history of skateboarding through video clips. The writer realizes that these video relics show skateboarding to be an act unparalleled in self-containment and visual definition. Filmed video parts are mimicry far more exact than what the writer can endeavor to shape with his words. Yet as the endless amount of footage expands to the point where there is more skateboarding online than pornography, the oeuvre grows nearly as difficult to navigate as the three levels of Central Park Hubba. Still one feels compelled to attempt success in the face of likely failure. Spirited conversation and literacy prove helpful as a way of determining what’s really good. One learns to trust one’s suppliers.

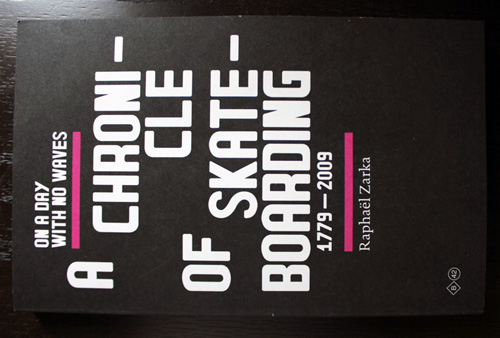

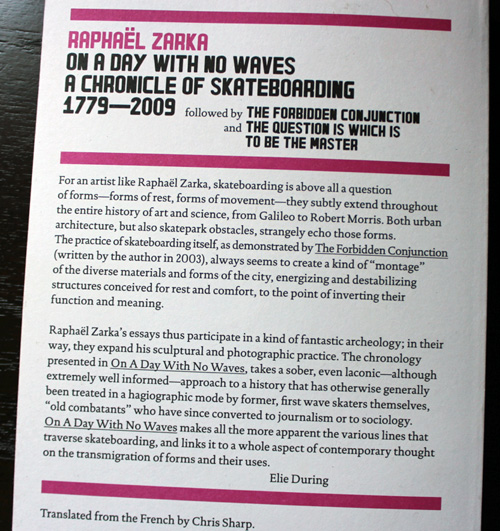

To examine skateboard literature into and beyond the industry canon of magazine writing is an autodidact’s game. Superstars have penned their life tales. Someone in Texas has channeled Justin Pierce’s ghost. The occasional coffee table edition may include a worthwhile introduction. To be aware of Skateboarding, Space and the City, by Iain Borden, shows that one has reached a plateau of skateboard reading. Due to the rarity of books in comparison to other skateboard media, the appearance of a new skateboarding book merits attention. With On a Day With No Waves: A Chronicle of Skateboarding, Mr. Zarka has chosen to document skateboarding’s history in a 230 year timeline.

There is pleasure to be found in reading Zarka’s chronicle in its entirety, as history does exist and ideas emerge through connections in linear time. In George Orwell’s 1984, a misled character claims that books are good to the extent that they reinforce thoughts the reader already believed. This chronology refutes such a claim, as the book is as its best when it prompts one to look beyond its pages, to perform research of one’s own on a subject of interest, much in the way a good skate video sends one outside, firecrackering off the curb, ready to do some tricks of one’s own.

The early entries of the chronology are those most likely to incite new research, both due to their remoteness from the present day and the more tenuous connections to proper skateboarding. As the title suggests, Zarka charts a path of skateboarding that evolves as man did from the ocean and lists a few premiere documents of surf literature. Jack London introduced surfing to the American masses in an inspired piece that shows his success where Mark Twain failed. Gidget, by Frederick Kohner, is an excellent novel that explores the ways in which a novice female surfer integrates herself into a predominantly male pastime. The chronology may receive attention due to its early beginning date, and the first 150 years passes in five pages, mostly surf related notations crossed with attempts to make ice skating a year-round activity. By 1950 we stand proudly on our pedestals, with four wheels between our feet and dry land as skateboards have become a commercial product.

Fine visual artists were quick to realize the aesthetic appeal of skateboarding and its tendency to draw the female eye. Skater Dater is neither Cassieopia Coane’s detailing of her relationship with The Pope of Spring Street, nor Flip Nasty’s modeling debut in the company of various LES based bachelorettes, but rather a silent, black and white short film that won the Palm d’Or at Cannes in 1966 and may be, along with The Red Balloon, an inspiration for Eli Reed’s forthcoming directorial debut.

“Lords of Dogtown” is an article by Greg Beato that appeared in Spin magazine’s March 1999 issue. Zarka describes it as “somewhere between a screenplay by Harmony Korine and a novel by Kem Nunn.” This piece acknowledges the challenges of aging as a popular skateboarder, the difficult home lives of many now-famous pros and shows a surf shop that survived by also selling “lifestyle accessories such as vicodin and fireworks.”

As further proof of the ways in which research proves infinite, Beato’s article served as my introduction to Bunker Spreckels, heir to a sugar fortune and stepson of Clark Gable, who would scout pools with Alva in a limousine. Spreckels, as a psychedelic forefather to Lizard King said: “Surfing just seemed to be the only thing to do when you take a dose of acid. It was a hell of a lot better than sitting around in somebody’s room staring at them, thinking you were reading their mind or having some kind of hallucinogenic tangent.” Much as Jack London and Mark Twain would have skateboarded had they been alive, F. Scott Fitzgerald wishes he had lived in a time that would have allowed him to chronicle Mr. Spreckels’ amazing exploits.

Followers of skateboard media in the past decade may be nearly completely familiar with much of the content from the mid-90s on into this millennium. With no entries longer than a page in length, any query on a subject familiar enough to look up in the index will be unlikely to include rare information. Yet the breadth of sourcing is remarkable. Zarka mentions product development, evolving terrain preferences, how skateboarding developed its dangerous reputation, musical trends, skateboarding’s appearances in mainstream media, teams, contests, video, book and art culture. Although skateboarding is a well known path to degeneracy, a document such as this provides a rounded course of study that may lead to further development of the gentleman skater type explored most fully in America by Ted Barrow.

In his addendum, Zarka notes that he tries to maintain a tone of impartiality, so perhaps fittingly the prose is at its most memorable when Zarka’s voice steps out from factual narration to offer an opinion or illustration of a trick. To carve is to “use the suppleness of the trucks to turn while keeping all four wheels on the ground.” Flip’s Sorry “lacks personality.” Zarka claims that Paul Rodriguez’s “contract of several million dollars earns him the nickname Paul Dollariguez.” An internet search into the popularity of this nickname turns up one result, coined by a commentator named “Dude.” Zarka has indeed mined the internet for the smallest traces of skateboarding apocrypha.

One senses that as beneficial of a document as this chronology is, it is not the medium in which Zarka is most comfortable. In Zarka’s career as an artist, he has made an extended exploration of the mechanics of architecture, the species of skateboarding spaces, and the ways to classify the act of skating. At the end of the chronology are two examples of Zarka’s theoretical prose, “The Forbidden Conjunction” and “The Question is Which is to be Master,” both of which are high grade considerations of these same ideas. This second title shares its name with a French short movie released in conjunction with Zarka’s essay.

The teaser shows a skater sessioning and traversing Paris, while Zarka appears on a radio program as the voice of skateboard theory, as a lovely girl who should date the author of this piece listens to the radio programme in a cab and talks with her driver about the difficulty of dating a skater. This mixture of elegant skateboarding and difficult romance charms the party boy in me, so I take the 30-minute, helpfully subtitled plunge with immediate pleasure.

While a skater’s video part is immediately dated, this relentlessly contemporary story never forsakes its skateboarding roots while transcending the genre of skate film to become a formal video art document. It hints at what Zarka means in his critique of Flip’s first offering. The skateboard video may be a more malleable format than a conveyor belt of rider parts split between introductions with a hallucination scene toward the end. A new twist on the old format may prove as inspiring as a trick taken to its largest obstacle. This film is an accessible introduction to Zarka’s work that you may as well watch and rewatch while waiting for the mail to deliver his chronology, which is a worthy addition to any skater’s bookshelf.

Released January 2011. 152 Pages. ISBN: 9782917855195.

Purchase the book at ÉDITIONS B42

Related: Grey Skate Mag interview with Raphaël Zarka

dope!

hey galen

really well written review! i really enjoyed reading this book, but remember the answer is never? i think jocko weyland wrote it a while ago, it had a photo of julien stranger on the cover, photo by tobin yelland.

http://www.amazon.com/Answer-Never-Skateboarders-History-World/dp/0802139450

that was an amazing text, it really blew my 20 year old mind, and probably still would. but maybe bc i have removed myself a bit from skateboarding or maybe just grew up, zarka’s book felt different. not in a good/bad kiind of way, but it felt more objective, more research based. i also really enjoy your ending line, reminded me a bit of one of the quotes on the back of skateboarding, space and the city, by big brother.. “a fine book that I recommend to any skateboarder who can read at college level”. superb writing..

anyway, great review, thanks for keeping skateboarding awesome,

ps yes i have been skating regularly now, in berlin.

good looks Vik.

After abstaining for a variety of situational reasons I just bought The Answer is Never.

I thought of you when I wrote this review, particularly when Zarka mentions Der Laufe der Dinge (The Way of Things) http://vimeo.com/7198223. “I wonder how many people other than early TF posterboy Viktor Timofeev will watch this video in its entirety” is an unused line.

raphael zarka is rad. just his few sentences about the rise of “skate plazas” and decline in real street skating in an interview on the greyskatemag site is worth more than the majority of skateboard media outlets combined. looking forward to finding this book, thanks for writing this review

What up Viktor!

tulip parlor!

That was really good. Thanks for posting it. Les flips trois soixante c’est magnific.

HELL YEAH MAN

For the record…I was in Skater Dater and it was in color. There is no dialogue but there is a sound track (surf music of sorts). Although it won the Palm d’Or at Cannes in 1966, It was also nominated for an academy award FWIW. Make no mistake The Imperial Skateboard Club who are featured in Skater Dater were the best free form skateboarders of that time. I don’t care what Woody Woodward might tell you (LoL). We were also independent from sponsorship. Started with two by fours and metal roller skate wheels, then “shaped” mini surfboards with clay wheels and finally the Hobie fiber-flex. We skated anywhere and everywhere and always barefoot.

Mr. Gary Hill: Thanks for sharing. I’ve been a fan of the film Skater Dater for decades. The point of the film is not as important as the historical documentation of The Imperial Skateboard Club of Torrance and Redondo Beach. You guys were awesome. I have fun every time I watch you guys do your stuff in Skater Dater. No doubt that the barefoot skateboarders with absolutely no safety equipment were the trailblazers.